{J} 29: A curious traveler's guide to CDMX Architecture

Part 1: Gothic, Baroque, and Neoclassic

People who land by night in Mexico City feel like they’re descending into cinema.

White lights twinkling across unlimited black, the blue beamed lasers of some outer-colonia fiesta, fire threatening on the volcanic horizon—a Latin American Bladerunner, a possible future.

Future, futuristic, futural: these are not words typically used to describe this metropolis in a high valley, which was pre-Columbian before it was viceregal, rococo and Austrian before it was Porfirian and French, and post-revolutionary before it was post-modern.

Rather, most people come here for the past—what Tenochtitlan was, what Teotihuacan was, who Diego and Frida were, before sitting down to a timeless dinner of taquitos gentrificados—as though the cultural collision that has happened, and the culinary fusion that is happening, will always be more important than what will, one day, occur. I mean it’s not like, in the popular imagination, Mexico City embodies something that gestures toward what one day might be, like the corporo-creativity of New York, or the high-cheeked, high-Mansard elegance of Paris, or whatever’s happening with Mumbai’s Saracenic-Decocore. Rather, as Gonzalo Celorio Blasco wrote in City of Paper, “The history of Mexico City is the story of its successive destructions … as though our sole permanence lay in the constancy of our annihilation”.1

And, well, jeez, there’s something to that, look around. Little annihilations everywhere!

A gleaming supermarket across from a burnt-out mansion, marbled apartments squeezed between greasy tire shops, an abandoned cloister held up by a pastelería, to say nothing of that abused temple poking out from a hole in Centro. The history of collapse is everywhere visible. Recently I was walking with a visiting friend on Reforma, the city’s most iconic boulevard. “Woah,” he said, turning right then left like a confused John Travolta. “This used to be a lake?”

Crazy, right.

And now it’s miles (and miles) (and miles) of buildings. There are so many buildings that, having filled the valley’s basin, they splash up against the sides of the mountains, their twinkling lights a pointillistic imitation of the lake that used to be. When I say descend into cinema, this is what I mean. Passing below the mountain rims at night, you’re flying between the city’s own stars.

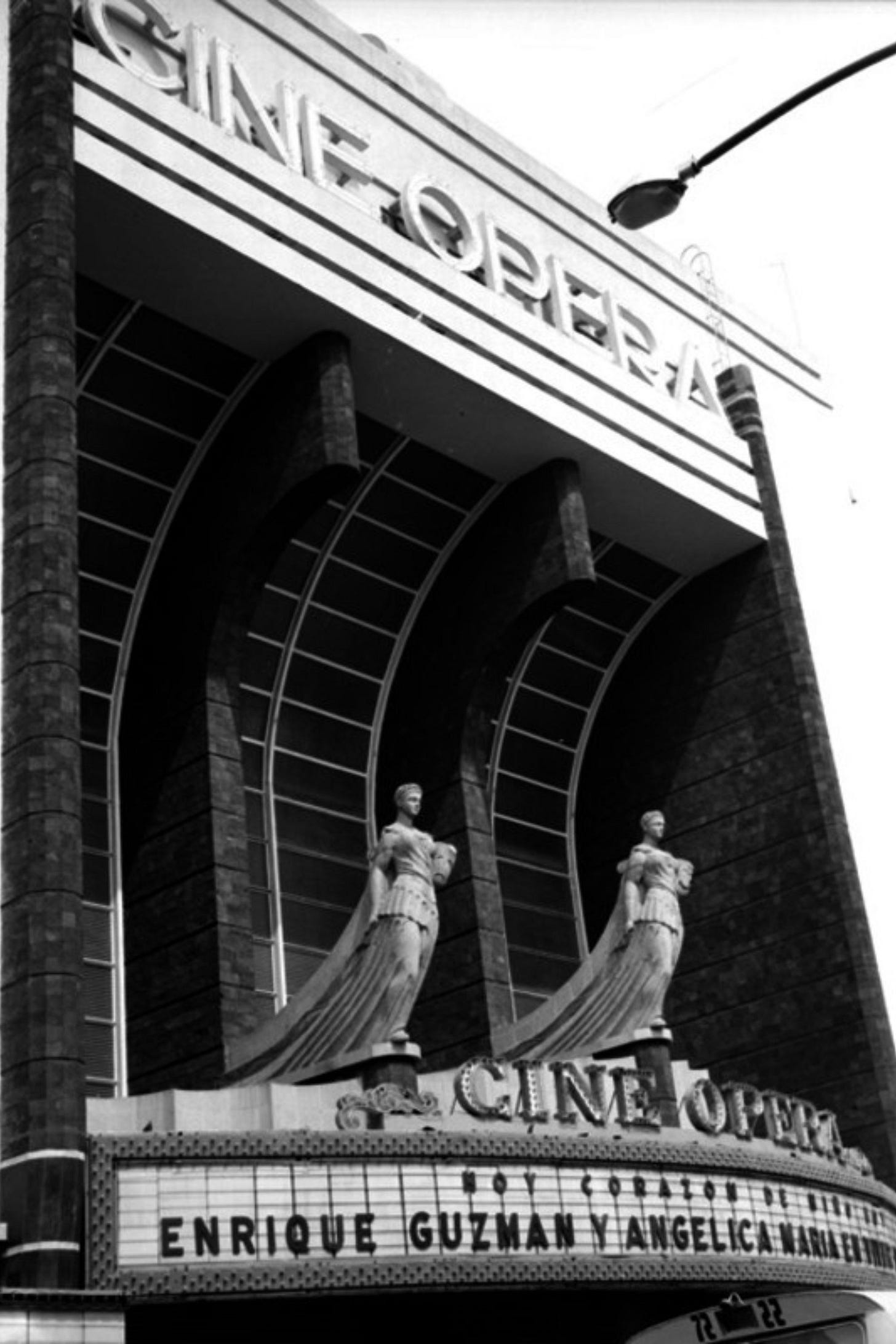

Let’s look around: here an art deco apartment building, there a beaux arts department store, churches upon churches in darkly florid baroque, modernist skyscrapers, not to mention muck-stained glass office buildings in the international style, that architectural equivalent of ¯\_(ツ)_/¯. Mexico City is different from Western capitals that way. You won’t find a single street in the city center where all the architectural languages align, where everything is all “of a piece”. There are pockets where styles are sorta contiguous. Condesa has an abundance of streamline depas. Las Lomas has an abundance of eclectic jardines. Escandon has block upon block of semi-brutalist apartment buildings. But taken as a whole, the city feels as though it has been woven by different seamstresses. Or, better, it’s the built equivalent of that Indian parable: The one where five blind men touch different parts of an elephant—the trunk like a snake, the leg like a tree—and come away thinking the animal is something entirely different than what its contiguous whole, en final, is. How did Mexico City become this collection of architectural odds and ends? Per Celorio Blasco: what had to be destroyed for each of these different styles of buildings to be created?

The block where I live, in Colonia Juárez, provides a good case study. This was one of the first planned colonias outside of Centro. Used to be street after street of manors for the city’s wealthiest. Most of it was burned down during the Revolution. What wasn’t burned fell in on itself during one earthquake or another. So next to my apartment is a tin-roofed bookstore (c. 1980) slapped against a proud Porfirian mansion (c. 1905), next to a crumbling vecindad (c. 1940). Across the street is a parking lot where a functionalist apartment building once collapsed, taking with it Rodrigo Rockdrigo González, Mexico’s Bob Dylan, on September 19th, 1985.2 Across from that is a shimmering white art deco apartment, balconies lined with cacti, standing there for almost one hundred years. Annihilation and rebuild, annihilation and rebuild, annihilation and repeat.

You won’t be surprised to learn that this pattern began with the Conquest.3 The conquistadores, builders of grim gothic things, built the grimly gothic Church of Santiago Tlatelolco on the site where the Aztecs, as the story goes, resisted most forcefully. The first stone was laid 1534. Churches, back then, were fortresses against a (rightfully) aggrieved indigenous population, and so many of the earliest colonial buildings, like the Monastery at Acolman, had a thick, unadorned, hunkered down posture. But the Spaniards carried with them the artistic baggage of the Isabelline Gothic and the Mudejars, and as they flattened Aztec palaces they built Renaissance iglesias with more balanced proportions, prominent tilework and plasterwork, and classical motifs. When you see what looks like Moorish design influences, that’s a good sign you’re looking at a Renaissance era building (or a revivalist copy).

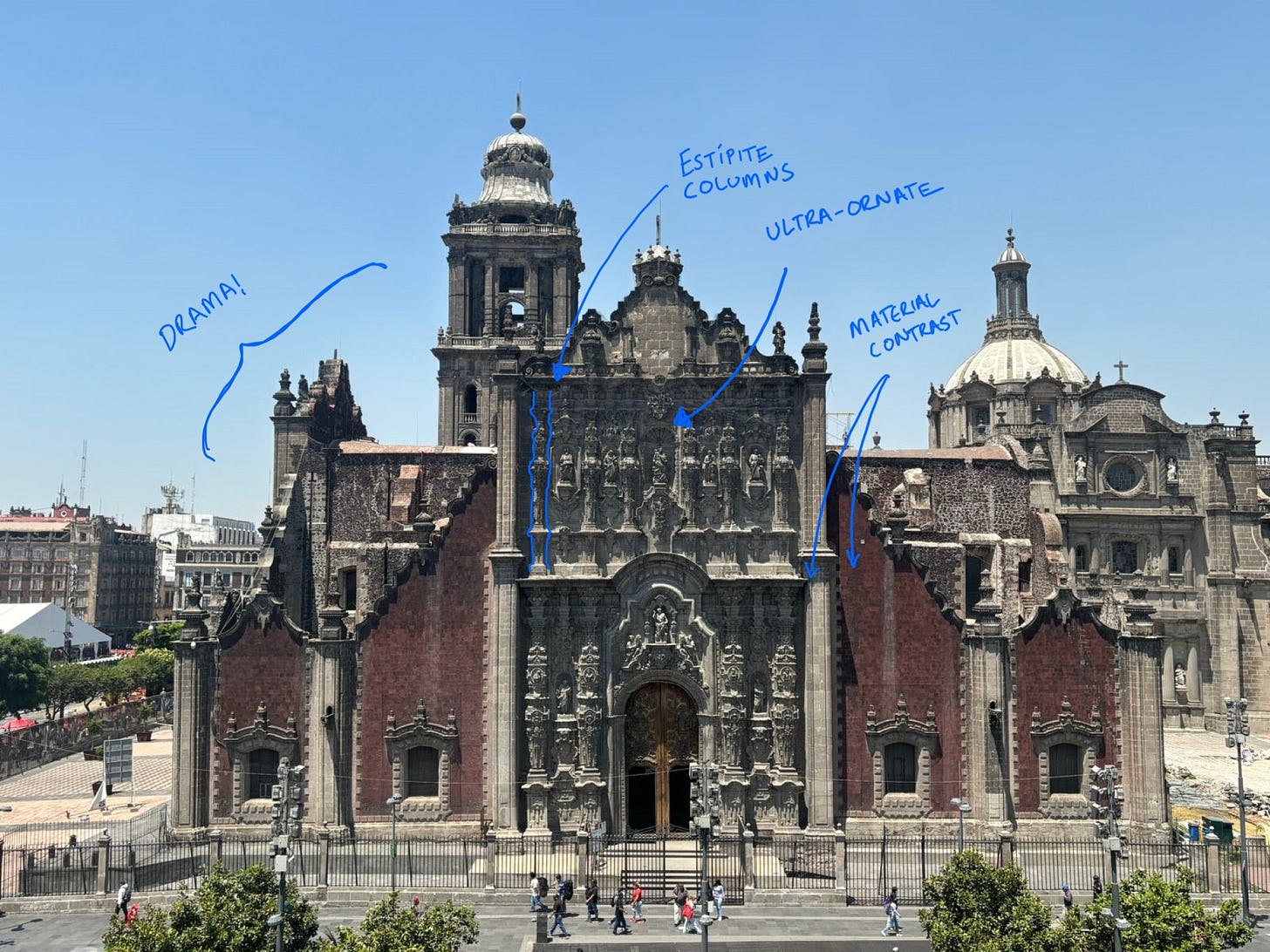

By the mid-17th century the Renaissance style gave way to the Baroque. Derived from the Italian barocco, meaning impure, bizarre, and daring, Baroque was a reaction to the austerity of the Reformation. It was designed to inspire awe with lavishly decorated domes, interior woodwork that looked like it was writhing, and exterior masonry that undulated in folds, columns, and cornices. Today I’d like to think we would describe Baroque as extra—bigger domes, grander colonnades, fancier portals. Basically, the RuPaul of architecture. Over the next century and a half, the style evolved from relatively austere (see, e.g., the constrained exterior decoration of the Church of San Lorenzo, designed in 1650) to positively whack-a-doo, e.g., the Sagrario Metropolitano, finished in the 1760s, and which is so disturbingly detailed it reminds me of the haunted masonry in The Devil’s Advocate. And who built these ornate buildings? The indigenous and the indentured, shifting and cutting rock from their razed palaces, chiseling beatific niches into cornerstones their ancestors had placed. Beauty was in the eye of the disenfranchised.

And then in 1781, Spain’s Carlos III founded The Academy of San Carlos—the first academy of Fine Arts on the American continent and the beginning point of modern art in Mexico. The Academy’s professors taught Neoclassicism, then en vogue on the European continent, which rejected baroque ostentation in favor of simple symmetry, unadorned columns, and classic pediments, all in mathematical proportions with restrained ornamentation. And so, standing alongside the baroque churches in downtown Centro, you’ll see the stately facades of buildings like the Palacio del Marqués del Apartado and the Palacio de Minería. They make an odd pair, the acid trip of Baroque and the teacher’s pet of Neoclassicism, but that combination is what gives Mexico City some of its sui generis surrealism. Neoclassicism carried the colony into the War for Mexican Independence, the annihilation that drove the Spanish from Mexico once, if not for all.

That was the first 300 years of Mexico’s existence under Spanish rule, and below is our cheat sheet for that period of Mexico City’s architecture. Each section is designed to help you understand, at a glance, a building’s style and what that style tells you about the that building’s place in the city’s history. There is, as you might imagine, a lot of info to synthesize, so I’ll publish it in three parts:

Part 1: Colonial, Baroque, and Neoclassic

Part 2: Spanish Colonial Revival, Eclectic, Beaux Arts, Art Deco

Part 3: Functionalism, Rationalism, International, Contemporary

This is roughly a system of historical divisions corresponding to changes in style. We’ll cover pre-conquest indigenous architecture in a separate, future post. For now, we’re focused on the architectural styles you’re most likely to notice on a walk through the city.

The examples below in no way constitute a comprehensive guide to all instances of an architectural style, but merely a guide to some popular examples (here’s a Google Map to get you started). It’s also important to note that architectural styles don’t have precise beginning and end dates; they exist in conversation with one another across convenient temporal delimiters. Often, several styles exist at once in any given building. At bottom is a list of further reading, museums, and tours, all of which I heavily relied on to compile this guide.

But we started this letter talking about the future, and that’s where we’ll end. It’s pretty common to look at architectural movements and design vocabularies as evidence of the past—like dead languages no longer spoken, or a kinda-sorta rigor mortis of masonry. Another way to look at it, and the way I prefer, is to consider each design philosophy as a possible future. A built imagining of what could be.

Baroque was a vision of the future of god. Neoclassicism was a vision of an orderly future. Eclecticism saw a cosmopolitan tomorrow, Art Nouveau a time when all arts coalesced, Functionalism a useful and affordable life. And little spaceships is how I think of the Art Deco houses of Colonia Condesa, recently arrived from planet Fritz Lang, ready for embarcation. Every vernacular is an adjacent possible, an alternate reality, a what if. And anyway, the most convincing visions of the future are always architectural. The Brutalism of Gattaca and A Clockwork Orange, the modernism of 2001 and Inception, the list goes on. You can’t have a future without an architecture.

And you might say well, Mexico City isn’t any future I’ve ever seen. It’s not the flying car gleaming Jetson’s future! Or the hyper-tall steel phalanges of China! It’s dirty and the garbagemen use bells, there is a general and joyous Mr. Toadian lack of driving etiquette, and everywhere there are chili-caffeinated fruit vendors brandishing bullhorns. But that’s the trick of cleverly imagined futures. They feel lived in. The puttering gasmobiles in Looper, the rusted office buildings of Brazil, Jerome’s old wheelchair in Gattaca.

Or to quote the journalist and critic Juan Villoro: “The future is more credible if it’s already used.”

Here we are, 7,000 feet up, descending into cinema.

-s.

Gothic and Renaissance

16th to 17th century (1550-1630 approx) / The Conquest and Colonization / Medieval, Renaissance, and Moorish influences

How to identify:

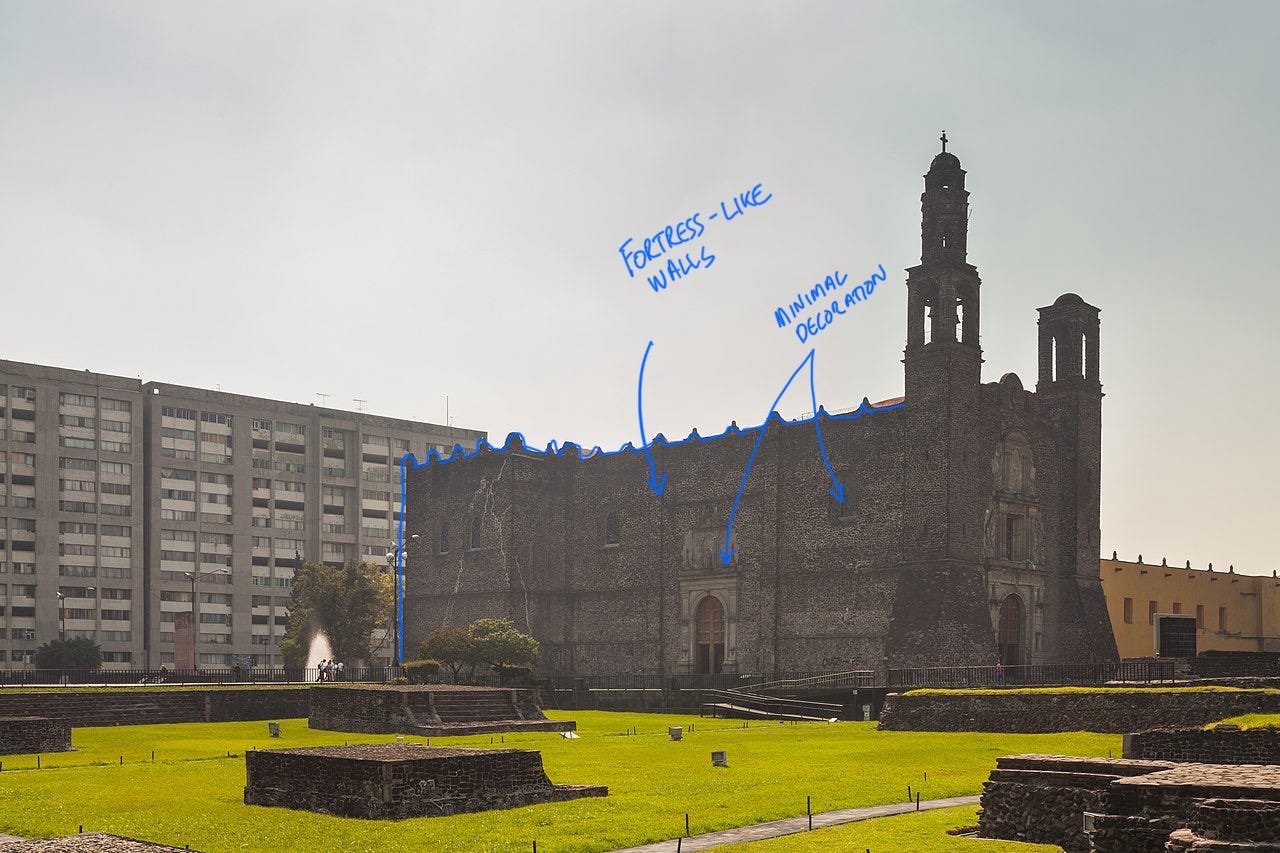

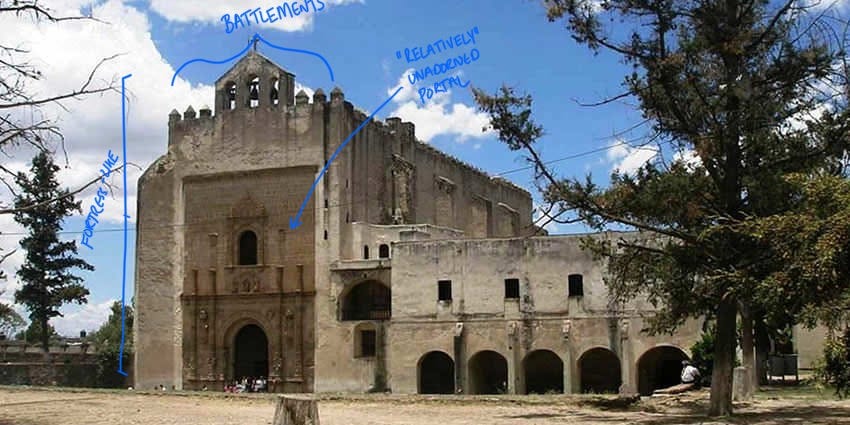

Look for fortress-like structures with thick walls made of reddish tezontle stone, minimal ornamentation, and heavy stone arches around doorways

Later buildings reveal Renaissance and Mudejar influence with more balanced proportions, rounded arches with keystone details, and ornamentation that includes medallions, rosettes, complex tilework and plasterwork, and classical motifs

The first buildings the conquistadors built were, basically, medieval fortresses—necessary, in a country that didn’t exactly welcome them. The process of conquest continued through the first half of the 16th century as the conquistadors spread out to subjugate the rest of the country, and the religious and civic architecture they left behind was necessarily medieval in nature: thick walls with minimal ornamentation, and single-nave churches often built with military considerations at the centers of unfortified towns.

After 1550 there were fewer dangers of uprisings and, thanks to the silver mines, fabulous wealth. The colonists began to build. The conquistador’s artistic baggage was Spain’s Gothic architecture, which was then under Renaissance and Moorish influence, thanks to the Mudejars (Muslim Christians in Spain) who provided Moorish ornamentation. That Mudejar style was applied to Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance architectural styles as constructive, ornamental and decorative motifs. In Spain, this was known as Isabelline Gothic, and this was the model when buildings began to be built in the Americas.

Examples (Google Map):

La Iglesia de Santiago Tlatelolco: The Church of Santiago Tlatelolco (begun 1535) shows strong Gothic influence in its fortress-like construction, thick stone walls, and minimal window openings that create a defensive appearance. Reflects the immediate post-conquest period when churches served dual roles as religious and defensive structures in potentially hostile territory.

The Monastery at Acolman: True church-as-fort. Built between 1539 and 1580, the walls are of rubble-stone construction and topped by battlements, giving the appearance of a fortress. One of the earliest and most ambitious examples of late Renaissance architecture with Gothic elements and Moorish paneling.

Catedral Metropolitana: Early construction, which began in 1573, shows Gothic influences in its basic three-nave layout and soaring vertical space. However, Renaissance elements quickly dominated: the façade features classical columns, balanced proportions, and geometric harmony typical of Renaissance design. The exterior is fancifully Baroque and its adjoining building, El Sagrario, is an excellent example of Churrigueresque.

Casa de las Ajaracas: The building that today houses the Photography Archive Museum was built at the end of the 16th century and owes its name to its Mudejar plasterwork. Sections of the building were destroyed and others rebuilt in earlier centuries, but including it here for the plasterwork that identifies it with Renaissance / Early Baroque.

Convento de la Merced: Built by the Mercedarian order, and one of the few extant examples of late Renaissance/early Baroque and Mudejar. Cornerstone laid in 1602, construction of the main church completed in 1654, mostly demolished in the 19th century. The cloister is all that is left of the original construction.

Early to Late Baroque

Late 16th–18th centuries (1630-1781 approx.) / The formation of the nation / European baroque, local aristocratic, and local cultural influences

How to identify:

Lavishly sculpted facades, highly decorative, theatrical, designed to evoke surprise and awe. Does it look like a wedding cake? Or like the building is orgasming in stone? That’s baroque!

The entrance portals of baroque churches tend to have semicircular arches, sometimes with broken pediments, flanked by single or double columns, with a niche or window directly above.

Lots of sculpture, both reliefs and figures in the round

Estípites, or truncated pyramidal columns. As the Baroque diverges from classical norms in Mexico and into the Churrigueresque, the aesthetic of columns increasingly featured vegetation, spirals, and other decorative motifs.

Baroque comes from the Italian barocco, meaning impure, bizarre, and daring. Begin by visualizing the domes and colonnades and portals of Renaissance architecture, then make them higher, more decorated, and more dramatic. That’s Baroque. Originating in the 16th century from the Catholic Church in Italy as a response to the austere architecture of Reformation churches, then spreading across Europe and into the Spanish colonies, the Baroque submerges the relative simplicity of fundamental architectural forms in, per Manuel Toussaint, “a proliferating fantasy.”

I mean, just imagine what it would’ve been like for a parishioner to experience a Baroque cathedral: a dome decorated with saints, altars embroidered with gold, priests vested in precious silks, and the worshipper on his knees, regarding the twisted columns, the soaring cupolla, and a simulacrum of heaven amid clouds of incense. Virtual reality for masonry, pretty much. Lingerie for bricks. Or maybe better said, the IMAX of architecture—you’re seeing the same movie, it’s just bigger, louder, and moving all around you.

Spanish Baroque developed its own varieties in Mexico from the late 16th to late 18th centuries, gradually growing more and more fanciful. The culmination of the Baroque style was the ultra Baroque or Churrigueresque, so-called after the Spanish Churriguera family, who made lavish altarpieces at this time. The main distinctive aspect of Mexican ultra Baroque is the estípite column—basically, an inverted, truncated pyramid, usually decorated with plants or spirals. The most famous example of this style is probably The Altar of the Kings inside the Metropolitan Cathedral, and the exterior main portal of the Sagrario.

Examples (Google Map):

The Church of San Lorenzo: Sober baroque, finished about 1650. Originally more Renaissance Mudejar in style, but the alfarje (paneled ceiling) was replaced with masonry vaults and a dome. Refurbished several times. The original columns are more neoclassic in style.

The Church of Santa Teresa la Antigua: Rich baroque, finished in 1684. Originally a convent. The two identical Baroque portals survive to this day, even as the building lists noticeably, not unlike a funhouse. Bring dramamine. Now holds the Santa Teresa la Antigua Alternative Art Center.

The Temple of San Felipe Neri: Commonly referred to as La Profesa. Rich baroque, designed by Pedro de Arrieta, finished 1720.

Colegio de San Ildefonso: The Colegio de San Ildefonso (founded 1588, built early 1600s) was originally Gothic, but has been almost entirely rebuilt. The building that stands today was constructed between 1712 and 1749 and is better an example early 18th century Baroque.

The facade of the Sagrario Metropolitano, designed by Lorenzo Rodríguez, finished in the 1760s, a great example of Churrigueresque (ultrabaroque).

Neoclassicism

18th century–mid-20th century (1781-1911 approx.) / Independence of Mexico / Rejection of baroque and French influences

How to identify:

Symmetry, simple columns, classic pediments, domes, all in mathematical proportions with restrained ornamentation

If it’s classical in form, with a very ordered and stately appearance that eschews a great deal of ostentation, it’s probably Neoclassic

Neoclassicism is what its name suggests: a rejection of baroque ostentation and a return to the proportions and clean lines of Greek and Roman architecture. Originally taking root in France following the discovery of Pompeii, the style was soon popularized in Spain after the ascension of Charles III who, like all good dictators, imposed a central authority to all matters of aesthetics, seeking to rein in the "bad taste" of the baroque with public buildings of "good taste" funded by the crown. Many of Madrid’s most famous Neoclassic buildings, including the Prado and Palacio de Liria, were designed during this time.

The heavy hand of Charles III extended, of course, to the colony of New Spain where, in 1781, he founded The Academy of San Carlos—the first academy of Fine Arts in the American continent and the beginning point of modern art in Mexico, where the professors taught Neoclassic forms. But despite Neoclassicism originating as the architecture of the crown, it soon became more associated with a rejection of colonialism. Mexico would rebel almost exactly 30 years after the founding of the Academy, and Neoclassicism would be interpreted as an artistic emancipation aligned with a political emancipation. Our guide Toussaint, however, was no fan:

“At the end of the colonial period … the Neoclassic movement, inspired by the Academy and its professors from Europe, presumes to extinguish the protean, chaotic life of the Baroque. It succeeds merely in producing monuments which are clearly importations and contrast miserably with the relics of the great preceding period. Yet it was then, within these very Neoclassic concepts, that Mexico achieved her independence.”

Well if you think Neoclassic and Baroque don’t go well together, wait till you see how they look alongside Modernism, friend!

Neoclassical forms would remain popular through the 19th century, melding into what historians call the Eclectic by the beginning of the 20th. Much of the architecture of the Porfiriato (1884-1911), for example, is neoclassic and eclectic, and inspired by Hausmann’s renovation of Paris, which began in 1853.

Examples (Google Map):

Templo de San Pablo el Nuevo, designed by José Antonio González Velázquez and completed in 1799

Palacio del Marqués del Apartado, designed by Manuel Tolsá and completed in 1805

Palacio de Minería, Centro, designed by Manuel Tolsá and completed in 1813

The Church of Nuestra Señora de Loreto, designed by Don Ignacio Castera and consecrated in 1816

Edificio Gaona, Centro (formerly a bullring), which can also be described as Eclectic because of the various styles used

Further Reading

Modern Architecture in Mexico City by Kathryn E. O’Rourke (Jstor, Amazon)

Colonial Art in Mexico, Manuel Toussaint (archive.org)

Mexican Architecture of the Sixteenth Century by George Kubler (archive.org)

Architecture in Mexico, 1900–2010 by Fernanda Canales (Amazon, Arquine)

The Mexico City Reader (Amazon)

📕 What is Julian’s?

Julian’s is a handbook for curious travelers written by Steve Bryant, who lives and works in Mexico City. Julian’s is named for his grandfather. The wordmark is designed in Frustro, a typeface inspired by the Pemrose Triangle, and which represents impossible objects—appropriate for Mexico City, which Salvador Dali once described as more surreal than his art.

The ongoing project of Julian’s is to create a print edition, bound and illustrated with original fold-out maps and featuring travelogue-style coverage of ten of Mexico City’s historic sights. Previous entries include:

The pavement of paradise

Handbook article #1: The Zócalo, the founding myth of Mexico, and a tour of the murals

We people here

Handbook article #2: El Templo Mayor

The cathedral that was a temple

Handbook article #3: a journey through Mexico City’s Metropolitan Cathedral

Or if you prefer an architect’s POV: “Mexican cities have been built on the basis of destruction: the center of New Spain erected over the ruins of Tenochtitlan, the late-eighteenth-century neoclassical city created over Baroque treasures, the liberal country of the nineteenth century overlying the viceregal heritage, the modern twentieth-century metropolis tearing down everything, and the twenty-first century now refusing to recognize twentiethcentury buildings as a legacy worth protecting.” Fernanda Canales, Architecture in Mexico, 1900–2010 (Arquine, 2013)

Chilangos will note that Rockdrigo was a long-term resident of Tlatelolco, but by ‘85 he had moved to Bruselas 8 en Colonia Juárez.

I’m concerned that you’re aware that I’m aware that architecture and art and etc didn’t begin with the Conquest, that the Mexica and their surrounding allies/vassals had a rich cultural heritage and built many impressive things. But I gotta put a cap on how far back we can go in one post. More on Mexica architecture in the future.