{J} 21: The Cathedral that was a Temple

Handbook article #3: a journey through Mexico City’s Metropolitan Cathedral

Hey friend and hola wey. This is the third article of Julian's Handbook to Mexico City, which takes the form of a westward walking tour from the Zócalo in Centro (the seat of Mexico’s government, and the former ceremonial district of the Mexica) to El Bosque de Chapultepec (the city’s largest park, where we end at a museum for the city’s waterworks). This is a “deep travel” guide for the curious traveler, a deeply reported and brightly written journey covering the city's major attractions while going deep on Mexico's history, religion, politics, and cuisine. Our goal: provide the same in-depth intelligence you’d get from a book, but in a brief and entertaining format. Julian's is a work in progress that we're building in public, with the goal of creating a printed guide. Thanks for reading. If you ever plan to visit Mexico City, I hope you’ll drop me a line. -s.Handbook Table of Contents

Julian’s Handbook to Mexico City covers the following:

The Pavement of Paradise

The Zócalo, the Bandera Nacional, and the jiggling, beating, passion-crowded heart of Mexico City“We people here”

The Aztecs, the temple, and the monumental island that was TenochtítlanCatedral Metropolitana

The cathedral, folk healing, Saint Death, and the history of Catholicism in MexicoEl Paseo de Reforma

A stroll down Mexico City’s main thoroughfare: built by the last emperor of Mexico’s to shorten his commute, paved by the last dictator of Mexico’s to burnish his reputation—to equal, he said, the Champs-ElyséesMonumento a la Revolución

What happens when you overthrow a dictator while he’s building a new houseEl Monumento de Cuauhtémoc

The tragic story of Descending Eagle, the first man to defend the patria from an invading armyEl Ángel de Independencia

Mexico City's most recognizable landmark is home to revelers, protestors, tourists, and the pilgrim bones of Mexico's heroes of IndependenceLos Niños Heroes

The Mexican-American War, the invasion of Mexico City, and the children fighters who, according to the legend, lost their lives defending their homelandEl Castillo de Chapultepec

Built by the man who gave the city of Galveston its name, later home to Mexico’s last emperor, and today a helluva art museum. More of a palace, really.El Carcamo de Dolores

The art museum (and terminus of an engineering marvel) where Mexico City celebrates its toxic relationship with water

Bright cloudless skies, whistling parking lot attendants, the clack-clack-clack of shop owners rolling up their corrugated metal shutters—this is Mexico City on a summer morning after an evening of rain has soaked the smog from the sky.

And that was the scene recently when, wanting to get some exercise, I rented an Ecobici and biked my way into Centro toward the cathedral.

I entered by way of Calle De Venustiano Carranza—named after the revolutionary era president, now a destination for buying sneakers, soccer balls, and sports jerseys. Each street in Centro has its own speciality—most of the sellers of socks on one boulevard, most of the jewelry stores on another, etc.—making downtown something of an open-air Wal-Mart, but instead of “children’s clothes” or “home goods” the aisles are named after revolutionaries and historical battles. I hung a left on Simon Bolivar (liberator of South America, printer and copier repairs) and biked past 5. De Mayo (military victory in Puebla, men’s clothing) to take a right on Donceles: former home to the conquistadors, now home to second-hand bookstores and the house cats who guard them. After parking my bike on a rack beside a six-peso public bathroom, I did some brief book shopping then walked into the Zócalo.1

One of the charms of the Zócalo, available to anyone who looks upwards, is the mixture of architectural styles: in this plaza, looking about, you can see an Aztec temple beside a Baroque cathedral beside a colonial era National Palace. It’s rare to find a similar combination of styles in the developed world, let alone at the site of a capitol. It would be as if, on the Great Lawn of Washington D.C., only a few yards from the colonial Capitol Building, you could tour a British statehouse from the reign of George III then stroll through a collection of Powhatan yihakans just next door. I circled the plaza for a few minutes, admiring a three-story tall golden eagle made of wire and tinsel that had been strung across Avenida de 20 de Noviembre (anniversary of the revolution, evening wear), then turned to regard, across the Zócalo, the twin towers of La Catedral Metropolitana.

It should be said that cathedrals in Mexico City sit on their haunches.

They’re magnificent, but their back walls sink into the soft earth and their faces incline towards the sky, like penitents waiting for a sacrament that’s slow to come. Look around: across from Alameda Central there’s La Iglesia de Santa Veracruz, half-submerged into the damp earth and tilting its eastern-facing walls towards the rising sun. A few blocks away there’s Oratorio de San Felipe Neri, a stony tower that leans towards the Zócalo, as if trying to join the tourists there. And two blocks beyond the Zòcalo there’s La Iglesia de Santa Teresa, whose stone floors slope so dramatically, this way and that, you’d think the church was about to capsize — much like the boat that brought its founder to Mexico, a near-death drowning which inspired him to build this sturdy Carmelite convent as if it were a dry dock for god.2 The convent now houses a museum for contemporary art where the projections on the walls only add to a sense of being tossed upon a baroque sea. Outside on the cobbled streets of Centro the walls loom over pedestrians or recoil dramatically backwards, while tourists crane their necks and adjust their cameras to comprehend dimensions. That’s the thing about this territory in a high valley. If the altitude doesn’t get you, the angles surely will.

The Metropolitan Cathedral, same same.

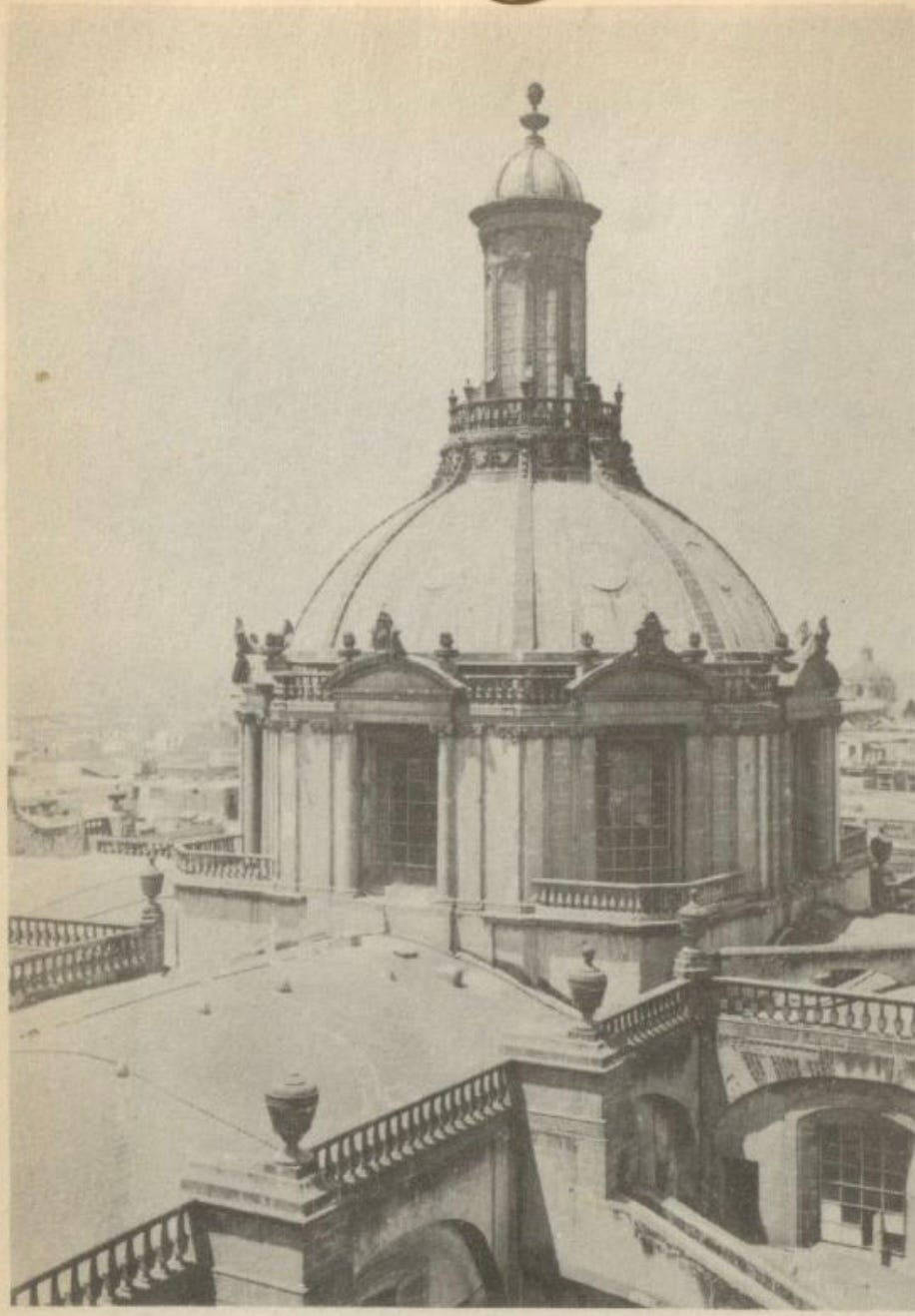

Formally, its full name is The Metropolitan Cathedral of the Assumption of the Blessed Virgin Mary into Heaven — where heaven, in this case, is presumably beneath the subsoil, as the cathedral sank an average of seven meters since its completion in 1816. To this day the cathedral leans slightly away from its adjoining sacristy, but the city intervened to stop the sinking in the 90s, calling on Italian engineers to use the same methods that prevented the Tower of Pisa from continuing its tendency toward the dirt. The cathedral now presides more steadily over the Zòcalo, a baroque bulk of chiluca, stone, and tezontle that holds, among other things, thirty tons of iron bells in its two towers and a pair of organs from the 17th and 18th centuries, the pipework of which weighs more than eight full-size SUVs. Heavier than heaven, to be sure, to borrow the name of a Nirvana tour. I guess everything must be.

“Una limpia?” asked a woman as I approached the stone and wrought iron fence that surrounds the cathedral.

She was wearing a breastplate of plastic skulls and black leggings and beckoned me towards a rug where a molcajete of smoking charcoal sat among branches of copal and pine.

A hundred pesos is the going rate for one of these limpias espiritual, or spiritual cleansings, but a charming visitor might talk them down to twenty. For that price you would then receive, from a man wearing an ocelot and peacock feathered headdress, a light brushing of a leafy branch around your body, water from a plastic bottle for your forehead, and a brief discourse on the four elements—el aire, la tierra, el fuego, y el agua—while the molcajete smoke wafts with the pleasant smell of rosemary and copal. “From old Mexico,” said one of the feathered men who approached, amiably but with his eyes half closed, whether from being tired or another kind of smoke I didn’t know. “For realigning the self to the natural order of things. When you are stressed, for fortifying the mind.”

A touristy gimmick? Nearby the whirling dancers in Aztec ceremonial dress and a drummer, beating a tumbadora in sweatpants, suggest a for-the-vacationer street scene. And yet chilangos stop by daily, queuing up to be cleaned of their ailments: bad energy, bad air, or even mal ojo. Some of the shamans are earnest curanderos, others charlatans, but all claim heritage with Aztec cosmology: that the body is linked to the universe, human behavior can affect the equilibrium and stability of the universe, and it is our duty to maintain the existence of the universe by recovering sacred essence energy that has left the body as the result of trauma. That sounds like hokum to some, ancient wisdom to others. But it’s a consequence of some amusement, to this writer at least, that it took us swimming in the 24/7 radio wave ether of the internet to appreciate that we exist in a matrix of connectedness with all other beings. Pre-Columbian peoples called it the universe. We call it vibes. 3

But in the moment I wasn’t thinking that. I was thinking: they seem like metaphysical ticket scalpers, these curanderos, working the crowd outside the cathedral and selling decidedly less Catholic seats to the great show in the sky: one where religion means harmony with nature, rather than protection from your own.

Declining their offers this time, I walked onwards past a thicket of sidewalk vendors selling relics that betrayed a more secular devotion. You can buy all manner of plasticos fantasticos here — sombreros and Rubiks Cubes in Mexican colors, knockoff sunglasses, friendship bracelets, necklaces, plushies of president Claudia Sheinbaum, carved jaguar skulls, crema de concha, caballitos, silicone kitchen sets, lucha libre paintings, much more — but I demurred and slipped into the cathedral, where I marveled at its high-domed immensity, its capacious silence, and its flat screen televisions, which suggest you follow the cathedral on nuestros redes sociales.

This cathedral took almost 250 years to complete.

Three hundred years, actually, if you count its lowly beginnings as a small three-nave church with a wooden roof, which Cortés ordered built in 1524 shortly after the Templo Mayor was razed.4 That church was eventually dismantled, but for decades this cathedral was built in sections around it, an unwitting analogue to the way the Templo Mayor had been built, each new layer burying what came before. In pantheism and Christianity alike, it’s churches all the way down.

Of course, this cathedral was built by thousands of indigenous laborers using the rubble of that temple. And who paid for the construction? One third the Spanish government, one third the rich peninsulares who lived in Mexico, and one third those indigenous villagers, the laborers not only paying tribute to the colonial government and the Franciscan convents but also shifting and cutting stone from the temple, cutting pine for the choral benches, carving estipetes and buttresses, and cementing the cloisters.5 To this day, the people of Mexico, including those descended from indigenous tribes, remain about 80% Catholic. Taking a seat in one of the pews and looking towards the soaring frescoes of gold that adorn the apse of the cathedral, I thought: Sunk costs, perhaps.

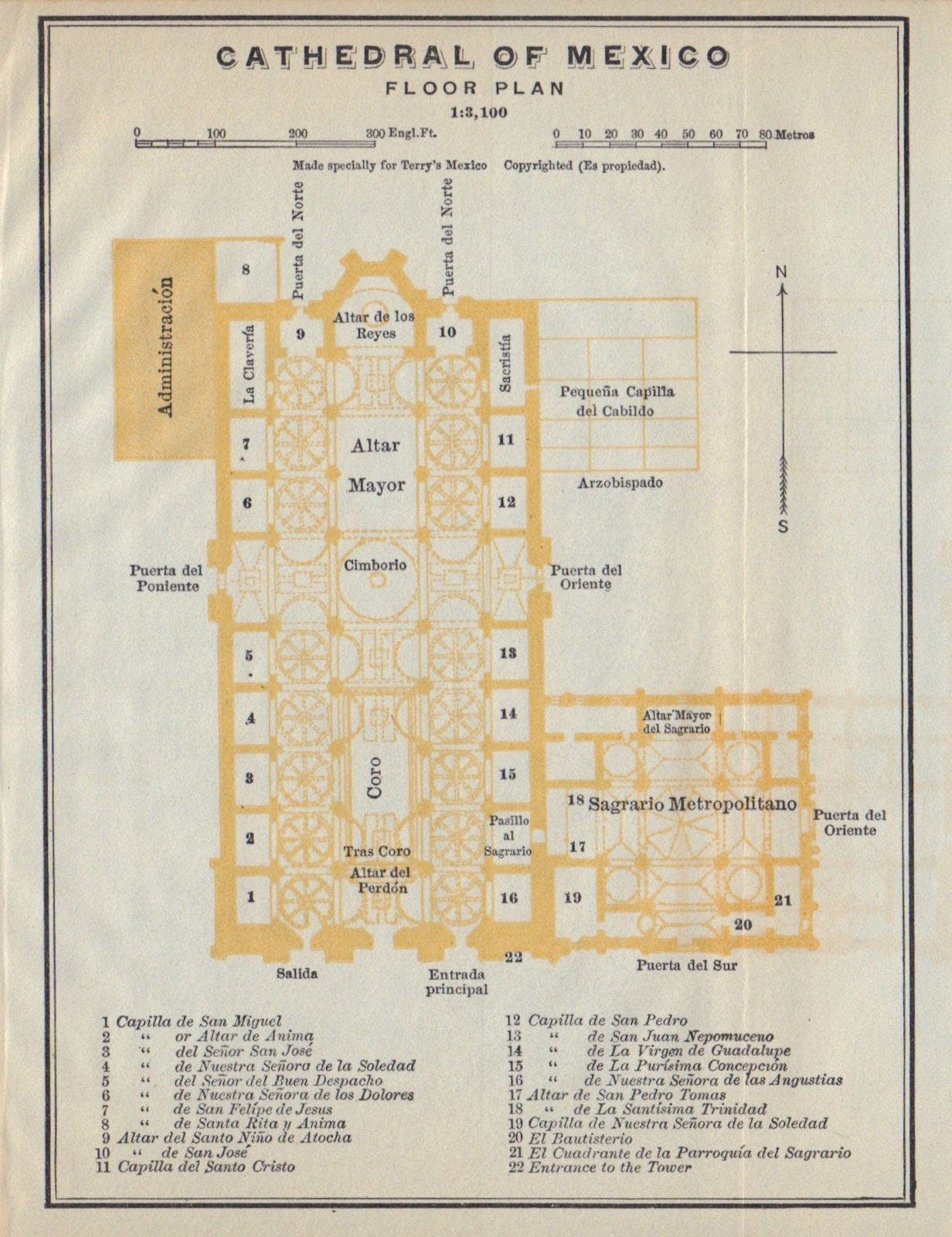

The sixteen chapels along the cathedral’s corridors, each dedicated to a different saint, together create a kind of Catholic Cinematic Universe for the curious and devoted alike. There’s La Capilla de la Virgin de Guadalupe, occasionally decorated with children’s toys in prayer for sick children; La Capilla de San Cosme y San Damián, with its wooden crucifix, the Lord of Health, which is invoked against epidemics; and Capilla del Santo Cristo y de las Reliquias where supposedly resides—among the bones of a thirteen-year old saint, the 49th pope, and the first-ever Christian martyr—a splinter from the True Cross and a thorn from the crown of Jesus.6

With time to kill, a curious visitor may also spend time regarding at least two other chapels, each with their own colorful stories to bring home. The first, in the passageway connecting the Sagrario Metropolitano, there’s Santo Cristo Negro, El Señor del Veneno, an icon of a black Jesus Christ on the cross that formerly resided in the Porta Coeli Church just a block south from the Zócalo. According to legend, a parishioner anointed the figure of Christ with poison to kill a priest who would kiss the figure’s feet every day—but, the next day, when the priest tried to kiss the feet of Christ, he saw that Christ bent his legs to save him from the poison, and then turned black.7 Hence, Holy Black Christ, Lord of Poison. “I beg you, Lord,” says a prayer printed on a sign near the image, “to purify me so that the vicious poison of sin not penetrate my heart.”

Across the cathedral, on the other side of the choir, you can find La Capilla de San Felipe de Jesús, the chapel of the first canonized saint native to Mexico. Sent to the Philippines as a young man to be a merchant, he entered the Franciscan order instead and began studying to become a priest. On his way back to Mexico to be ordained, his ship was diverted by a storm to Japan, where he and the other friars were imprisoned, hung on crosses, and then stabbed to death with spears.

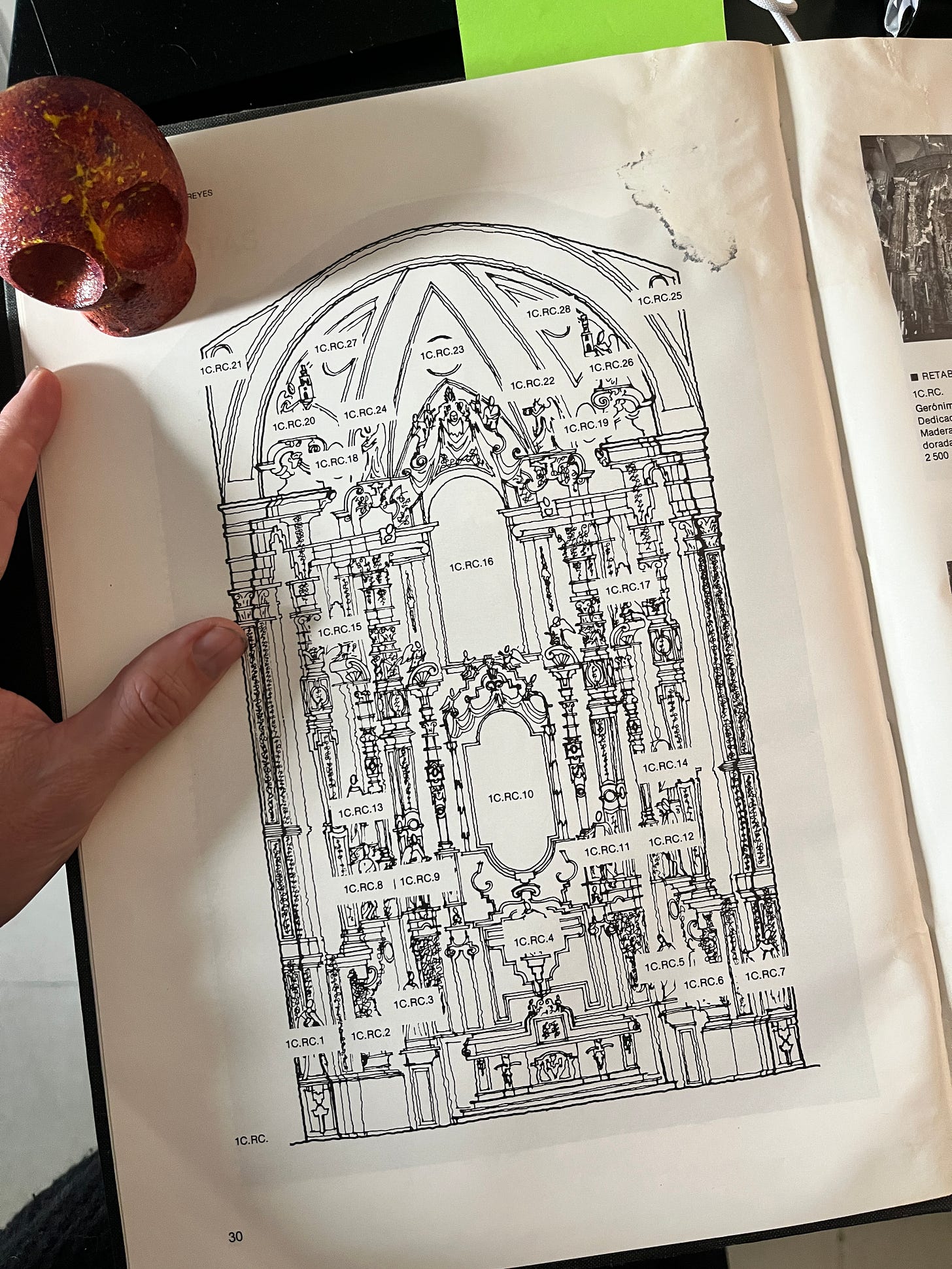

But it’s the towering Altar of the Kings that’s the real attraction here, an almost three-story tall “golden cave” that dominates the rear of the cathedral and is carved from white cedar wood in the Churrigueresque style, aka Mexican Baroque.

“Timid in the beginning, then daring, and finally mad” is how one chronicler of colonial architecture described the procession of all things Baroque, and the Altar of the Kings, hyper florid with cherubs and garlands and bouquets whittled into impossibly vegetative shapes, is the endpoint of that delirium.8 It’s a style that makes good sense for Mexico City, the Churrigueresque. This is not a territory known for its restraint, and the altar’s flamboyance finds an analogue in everything from the riotously loud streets, to the colorful buildings, to the city’s fauna that bursts across the sidewalks and parks. In other latitudes this vegetation would be manicured into shrubberies and domesticated into submission but here it explodes in fleshy green fireworks of monstera and maguey. Less a golden cave, more a golden jungle.

Earlier, I’d purchased at one of the bookstores on Donceles a thick and water-stained book about the cathedral which offered numbered schematics of the altar’s constituent parts. So, sitting in the pew and running my finger down that book’s yellowed paper, I learned that what I was looking at, through the woodworked leaves and fronds, are essentially two things: paintings of religious scenes, and effigies of canonized kings and queens. The paintings, darkened over the centuries to the hue of soot, depict two timeless Catholic obsessions:The Assumption of the Virgin and The Adoration of the Kings. The effigies, on the other hand, include not only the most recognizable figures from the Catholic Cinematic Universe, such as the apostle Paul, but also a selection of popular-in-the-18th-century saints who may seem a bit obscure now, the Catholic equivalent of forgotten Academy Awards winners. There’s Saint Margaret of Scotland, whose head was borrowed by Mary, Queen of Scots as a relic to assist in childbirth; Saint Casimir, the patron saint of Lithuania renowned for declining his physicians’s advice to have sex with women in order to cure his illnesses; and Ferdinand III of Castile, the namesake of the San Fernando Valley whose incorruptible body still lies today, in a state of fairly obvious corruption, in the Cathedral of Seville. The men are arranged along the top two thirds of the altar while the women, their eternal burden to support the pomp and frippery of men, stand Atlas-like along the bottom.

State-sponsored, Pope-approved: That was the project of colonizing the Americas, a partnered-up quest for silver to mine and non-believers to convert.

During the viceroyalty when this territory was called New Spain, it was customary to dedicate the main chapel of any cathedral to the crown, and the Altar of the Kings is no exception—hence the name, and hence this union of the political and the religious. It was the papal bulls of Pope Alexander VI in 1493 that confirmed the rights of the Spanish crown in the New World, shortly after Columbus discovered “Hispaniola”, but proselytization didn’t begin in earnest until the Spanish crown invited a dozen Franciscans to convert the valley’s tribes. The so-called Twelve Apostles of Mexico arrived in 1524, settling in Tenochtítlan and the surrounding villages where they learned Nahuatl, opened convents, founded schools, reorganized towns, and forcibly compelled the sons of Aztec nobility to learn Spanish.

How do we know what we know about the Aztecs? Those friars, mostly. Specifically: through the painted codices prepared by the Aztecs at the request of missionaries, usually with accompanying texts written in Spanish. Spain occulted Latin America for hundreds of years, forbidding most foreigners from entering, and so until the 1800s works like Friar Bernardino de Sahaguin’s Historia general de las cosas de la Nueva España were some of the only windows into pre-Columbian society in the Valley of Mexico. Books within Sahagiuin’s works, like the famous Florentine Codex, and others like the Annals of Cuauhtitlan and the Codex Mendoza, revealed the experience of the conquest by the Spaniards, Mexica cosmology, and valley politics. But, these were, by and large, texts through the eyes of Catholics with an apocalyptic zeal, who saw New Spain as the battleground between the forces of good and evil, who reaffirmed and exaggerated stories of sacrifice, bloodshed, cruelty. It was, of course, a dramatic form of myopia: While Friar Sahaguin was writing his Historia general, Spain was still burning alive the Moriscos, the Franche comte of the northern Alps, and countless Lutherans, Calvinists, and scientists. “Who controls the present now controls the past,” go some of Zack De La Rocha’s more famous lyrics. And who controlled the present and the past after the conquest? The Spanish state, the Catholic church, the Franciscan friars. It wasn’t until the 1950s and 60s that historians began to study the Aztecs and other Mesoamerican cultures on their own terms, from their own writings and points of view.9

But the Mexica didn’t just blindly accept the new Christian gods, they folded them into their existing beliefs.

Curbside shrines to Guadalupe, Day of the Dead celebrations, Catholic peyote shamans, Santa Muerte altars with figurines of Jesus, limpias performed with Christian prayers—such is the evidence of that syncretism today.

At first, the earliest Franciscans eagerly reported that the indigenous people were enthralled by Catholicism. Thousands were baptized, and the friars managed to convince the Western world that they had converted all of Mexico. And they did, kinda. “They all became Christians, at least nominally,” wrote Louise Burkhart in her famous account of the Nahua’s experience of the conquest, “but they failed to yield so easily to the friars’ attempts at cultural alchemy.” Instead, she wrote, they managed to turn Christianity into something of their own.

And famously so. A forty-five minute metro ride north, from the cathedral to the Basílica de Santa María de Guadalupe, will bring you to the second most-visited sacred site in the world. According to accounts, the mestiza Mexican Mary revealed herself to an indigenous man named Juan Diego on the hill of Tepeyac on the north side of Mexico City. This was 1531, less than a decade after the friars began converting the Nahua and the Virgin, speaking in Nahuatl, commanded Juan Diego to build the shrine. Reviled by the Catholic Church at first, Guadalupe was eventually canonized in 1887. To this day the most fervent worshippers approach on their knees.

The more adventurous traveler may, on their way north, wish to detour to the site of another saint, one whose popularity has begun to eclipse the Virgin but who will never be recognized by the pope: Santa Muerte, a.k.a. the skinny girl, a.k.a. la Flaquita, la Huesada, La Niña Blanca, the folk saint personification of death. Whether as a plaster statue, or illustrated on a prayer card, or as a six-foot effigy as found outside the home of Doña Queta in the cinderblock grim barrio of Tepito, Santa Muerte is often depicted as a female Grim Reaper wielding a scythe and wearing a shroud. Unlike church-sanctioned saints, folk saints are spirits of the dead considered to work miracles for their devotees, and they command widespread devotion: saints like Niño Federico, Maximon, and Jesus Malverde are often sought after more than official saints like Guadalupe or St. Jude. The majority of these folk saints were born and died on Latin American soil, and so they’re connected to Mexicans by the land and by social class. Accordingly, Santa Muerte is the patron saint of taxi drivers, prostitutes, street vendors, housewives, occasional telenovela stars, and the Mexican penal system. The life-size effigy outside the home of Doña Queta? A gift from one of her sons, who placed it there in 2001 to thank la Flaquita for his release from prison.10

Be aware: Tepito is a grim barrio of cinderblocks and paint, run by skulking boys and thin dogs, thick with sidewalk markets and the exhaust of idling mopeds. Known as one of Mexico City’s most dangerous slums and the stomping ground of gangs like Unión Tepito, these days it sees the occasional tourist. Most come, it seems, to see Doña Queta’s shrine, but others wander out from La Llagunilla, the Sunday antiques flea market, as they try to make their way back to Plaza Garibaldi’s cantinas. A thematic adventurer might consider it a station of the cross for Mexico City, a stop along a processional that travels from Christ in the cathedral, to death in the barrio, to the virgin on a hill. Keep heading north and you'll eventually arrive at a fourth shrine, so to speak – the border itself, la frontera, where cosmic miracles sometimes reveal themselves with a successful crossing. "Poor Mexico,” the Mexican president Porfirio Díaz once said, “so far from God, so close to the United States."

What, finally, does it mean to be religious in Mexico? The cathedral, like the Virgin of Guadalupe, like Saint Death, are only totemic glimpses of a deep-forested and mountainous religious feeling. And while you can visit these places, I’d also suggest that a more pedestrian pilgrimage would inspire wide-eyed devotion. A day for carts and carritos, is how I might begin, and a few days in pursuit of lemon-spiced beers in wooping cantinas. A week at least for museums, another for photographing art deco doors, another for inclining your head to view crumbling buildings dramatically askew, and markets selling vintage ashtrays, serviceable mid-century radios, and tarnished hands of Fatima. Several days, you’ll need, at least for Porfirian mansions and the technicolor church-homes of Barragan. An hour daily, minimum, to stoop under the bowed fronds of arecas and monsteras and palms. Reserve the appropriate hours for tripping on vertiginous sidewalks and ducking Telcel’s tendrils, which hang blackly everywhere you might walk, trying to ensnare you in their gossipy contents. And hours still may be spent regarding bell-ringing garbagemen, junk buyers in pickup trucks, aguadores pedaling rusting bikes with suspicious water, and frail tias performing, outside their doors, the holy act of sweeping.

Such are the true houses of worship in Mexico City.

📍Nearby dining and drinks

The government of Mexico City maintains an impressive guide to Centro Histórico Temples and Churches, so instead of recounting those, have a bite and a drink at one of the recommended spots below.

El Cardenal: Traditional Mexican cuisine, perfect for breakfast or lunch before (or after) visiting Bellas Artes and MUNAL. Several locations around the city.

Café de Tacuba: Founded in 1912 in a colonial style mansion and serving up traditional Mexican dishes in a gorgeous hall decorated with paintings from the era of New Spain and stained glass from Puebla. The café also inspired the name of one of Mexico’s most famous alt rock bands, Café Tacvba.

La Ópera: One of the city’s oldest continuously operating bars and restaurants, opened in 1876 and moved to its present location in 1900. According to tales, Pancho Villa fired a shot into the ceiling here during the Revolution. Sit at the bar, which was imported from New Orleans, for classic cocktails and traditional Mexican plates.

Tacquería Los Cocuyos: Historic taco spot famous for their “meat jacuzzi” of taco meats. Can’t go wrong with suadero.

Bósforo: Incredible mezcal bar. Light on the weekdays, packed on the weekends. Also serves food. Next door, La Vitrina serves delicious baguette sandwiches.

📚 Further reading

Catedral de México: a chapbook on the Cathedral in English, Spanish, Italian, and German by its most famous chronicler, Manuel Toussaint

The slippery earth: Nahua-Christian moral dialogue in sixteenth-century Mexico: foundational modern text by Louis Burkhart

Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint: truly comprehensive book on Saint Death and folk saint syncretism in Mexico

Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs: Required reading for anyone interested in the Nahua experience of the conquest

Travels in the New World: one of the first travelogues of New Spain by an English Dominican friar who snuck aboard his sailing vessel in a wine barrel. Long and not always entertaining, it remains an interesting account of Mexico from a time when foreigners were rarely allowed to see it

The natural history of the soul in ancient Mexico: Incredibly detailed work on the conception of the soul in pre-Conquest Mexico, including how the Spaniards attempted to translate those beliefs and how the native conception differs from the idea of the traditional European soul

Aztec medicine, health, and nutrition: Foundational academic study of how the Aztecs classified, studied, and treated disease

The Mexico City Cathedral (JSTOR)

The Virgin of Guadalupe: Symbol of Conquest or Liberation? (JSTOR)

For Spanish readers, see the incredibly detailed and colorful almanac to Centro: Miscelánea: Guía del comercio popular y tradicional del Centro Histórico de la Ciudad de México

The government of Mexico City maintains an impressive guide to Centro Histórico Temples and Churches.

There are an unending resources on spirituality in Mexico, but three I can recommend include two works of scholarship (The natural history of the soul in ancient Mexico and Aztec medicine, health, and nutrition), plus an interesting albeit new age-y, how-to book from a modern practitioner called Cleansing Rites of Curanderismo.

For a more complete timeline of the cathedral’s construction, see our previous post in Julian’s

After the conquest, Cortés awarded each conquistador the villages of a particular altepetl or sub-altepetl as an encomienda, or “trust”. In theory, the conquistadors were meant to guard the spiritual and political well-being of the people living there. In exchange, the people were to pay him tribute in labor and goods. But if it walks like a duck and talks like a duck, it’s a duck. The encomienda system was a duck called slavery.

Lots of bones, from at least two civilizations, are in (or have been in) the cathedral over the centuries. Perhaps my favorite treatment of Mexico’s relationship to bones and bodies is a the chapter “The Mausoleums of Heroes” in Juan Villoro’s excellent book of essays, Horizontal Vertigo.

There are at least three versions of this story. Choose your own adventure.

There are many histories written about the cathedral, but perhaps the most well-known chronicler is Manuel Toussaint, especially La Catedral de Mexico y el sagrario metropolitano: su historia, su tesoro, su arte, original copies of which sell for several hundreds of dollars.

I’ve said it before, but a great secondary source for learning about the Nahua experience before, during, and immediately after the conquest is Camilla Townsend’s Fifth Sun: A New History of the Aztecs.

In Mexico, Santa Muerte entered the public consciousness in the 90s, after an altar was found in the home of Daniel Arizmendi “The Ear Chopper” López: a police officer turned kidnapper who sent the ears of his victims to their families in order to elicit payment. But it wasn’t until 2001, when Doña Queta’s son gifted her a statue of Santa Muerte after his early release for prison, that her fame began to steadily increase. For foreigners, the introduction came later, via screens: Breaking Bad most famously, or Better Call Saul and Narcos, each depicting, via candle-covered altars, her storied association with cartels. It’s estimated that 5% of Mexicans worship her, though you’ll likely find her to be a thema fejo among most acquaintances. It’s not like she’s hard to find, though: the Tepito altar, after all, is on Google Maps. A less perilous introduction to her mythology, and the world of Mexican curanderos, can be found on aisle nine of the Mercado Sonora. For a comprehensive history and analysis, see the excellent book by Andrew R. Chesnut, Devoted to Death: Santa Muerte, the Skeleton Saint.