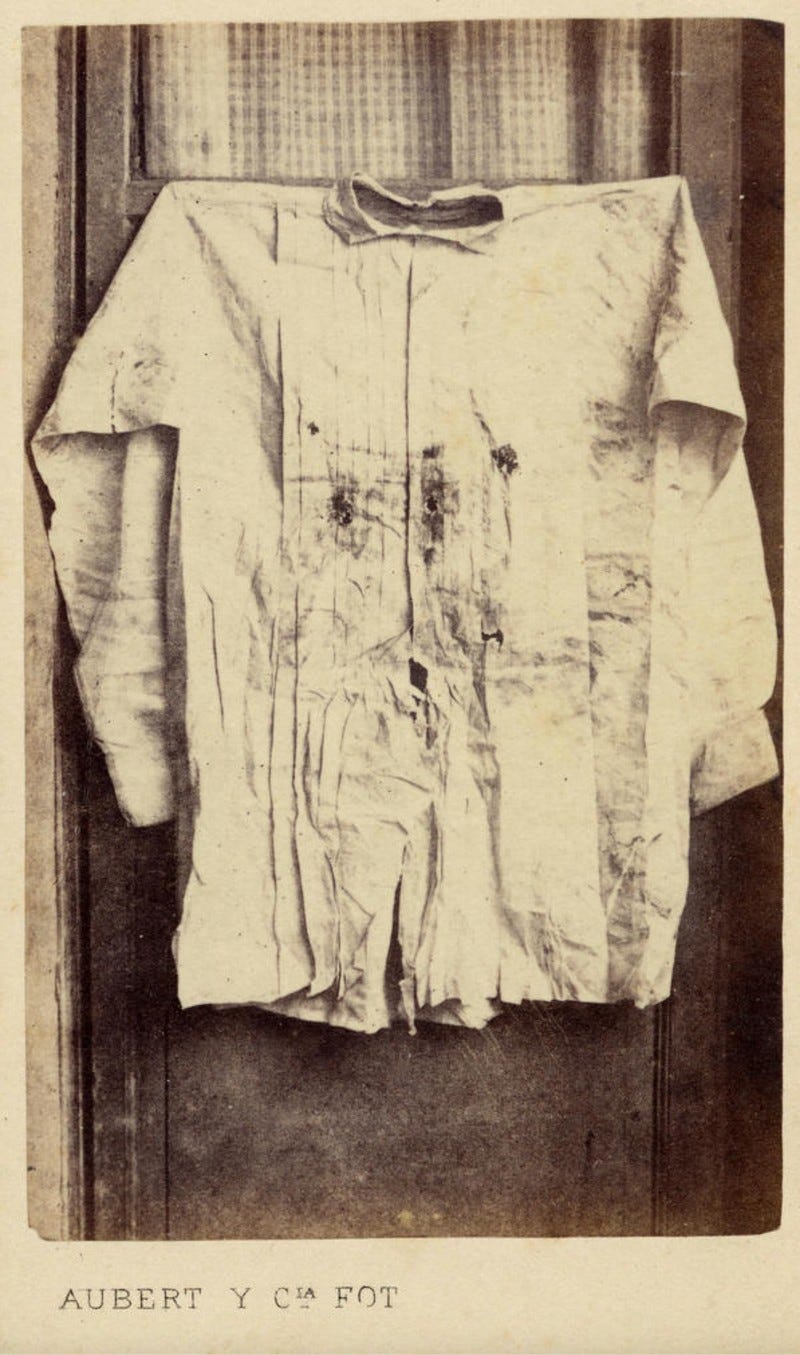

The shirt of the emperor, worn during his execution

All about a yellow sewer horse and the invention of the term "Latin America"

Across from my apartment in Colonia Juàrez, there is a clean and well lit bar that sells $20 negronis. That bar is next to a rarely swept plaza where Haitian migrants sleep. At night their cell phones light their orange tents from within.

Some of the nearby streets are named for European capitals. On Roma, there are no Italian baroque buildings, but there is a Spanish colonial mansion. It leans against a cinderblock ferretería and a black sleeve of a bike shop, where sparks skip like pennies into the street. On Londres, filled with South Korean restaurants, Americans work on Macbooks next to Mexican families making tacos de pastor, a Moroccan way of preparing meat.

The charm of every city is its conceptual contrasts, sure, but Mexico City takes it to a fetishistic extent. Maybe you remember the launch of Dall-E-2, when your feeds were filled with unexpected visual mashups. There was a medieval painting of the wifi not working. There was a photo of Homer Simpson in Psycho. Anyway, the other day walking in Centro, I saw a Hampton Inn and Suites stuffed inside a Neo-Colonial manor. Moments like that were enough to make the real Dalí wince: “There is no way I’m going back to Mexico,” he is reported to have said. “I can’t stand to be in a country that is more surrealist than my paintings”.

Makes you wonder what he would’ve thought about the Mexican Empire. In last week's letter about Chapultepec Castle, we touched on how Maximiliano (an Austrian prince) and Emperatriz Carlota (a Belgian princess) were installed by the French on the Mexican throne for three years, 1864 to 1867. European monarchs are familiar to Western readers, but the idea of a monarchy on American soil sounds so strange, you’d be forgiven for considering the whole affair to be metaversal fiction, belonging to that class of entertaining hypotheticals like Marvel’s What If …?, The Man in the High Castle, or If the South Had Won the Civil War. But it’s true. Fecund Mexico, sub-tropical Mexico, yellow fever and maguey Mexico, land of sweet skeletons, was ruled by a rigid and horsebacked people, dressed in ball gowns and epaulets, martial and orthodox. If you had to pick two Western cultures from the 19th century to mash together, you'd be hard pressed to find a more opposite pair. Which makes the curiosity of how it happened all the more enjoyable to relate.

An Austrian Hapsburg in President Juárez’s court

After 300 years of Spanish rule, Mexico gained independence from Spain in 1821. In a rhapsody of political mitosis, the country promptly divided itself into liberals and conservatives, the latter of which had a monarchial faction. This made a certain sense, as Mexico’s first choice of government after ridding itself of one monarchy had been to establish another: Agustín de Iturbide, an officer in the Spanish army, switched sides during the War of Independence and fought to overthrow his Iberian lords, then proclaimed himself monarch and ruled for little less than a year until he was forced to abdicate. He was exiled but then, in a final display of his defining characteristic, changed his mind. He returned to the country and was shot in 1824. Conservatives, inspired by this great success, continued to see monarchy as a viable option.

Really they were just tired of war. For forty years after Iturbide, liberals and conservatives fought for control of the Mexican government, during which time no less than 25 leaders revolved in and out of office as they fought revolutions, abdicated, or died. When, in 1857, the liberals finally succeeded in getting a new constitution ratified, conservatives declared that constitution invalid and formed a rival government, leading to a three-year civil war that was won by the liberals—on the battlefield, at least. Conservatives regrouped and sought external allies for their monarchist cause.1

Meanwhile in Mexico City, the liberal government was being led by Benito Juárez—to this day, Mexico’s only indigenous-born president, and the only leader to have his own national holiday.2 The problem for Juàrez’s government was, after three years of war, they were broke. Struggling to impose national order and strapped for cash, Juàrez suspended Mexico’s debt payments to British, Spanish, and French creditors. This did not please the emperor of France, Napoleon III.

For the uninitiated, Napoleon III was the nephew of Napoleon Bonaparte—not the military leader who joined Bill and Ted on their Excellent Adventure, but the popular statesman who, among many other accomplishments, transformed Paris from a choleric backwater into a picturesque city beloved by basic white girls everywhere.3 Napoleon came to power in France after a failed coup at a garrison in Strasbourg, a failed coup at a customs house in Boulogne, an escape from prison while disguised as a laborer carrying lumber, and eventually an election, whereafter he assumed the modest title of Prince-President, did a coup against his own government, and made himself emperor. Ambitious fellow. That ambition included influencing the Western hemisphere, where he hoped to counter the growing power of the United States by gaining suzerainty over “Latin America”—a term, btw, which was invented in the 1850s to rally southern Catholic people against the anglo-saxon Protestants of the U.S. Influenced by his wife and Mexican monarchists4, Napoleon Number Three decided to use the issue of loan repayment as a pretext for invading Mexico and installing a friendly government. For that job, Napoleon picked Maximilian.5

Placing people on thrones, especially Habsburgs, was a time-honored European tradition.6 Max, in this Mendelian regard, had impeccable credentials: he was a descendant of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor during the 1521 conquest. Second, he was Catholic, which had been the Mexican state religion ever since Cortés razed the temples of Tenochtitlan and built churches above them. And third, most importantly, he was available: Maximilian’s older brother was the emperor of the Austrian Empire and so he, the second son, had no formal role. Max, encouraged by his wife, accepted the offer.

It’s important you get a good picture of Max: an archduke in the royal house of Habsburg, one of the oldest dynasties in Europe, Max grew up with memories of their imperial glory and inside palaces decorated with the acrostic AEIOU—Latin for “All the world is subject to Austria”. As a child he was schooled for eleven hours a day (including by Hans Christian Anderson!) in literature, history, horseback riding, and martial drills. He spoke five languages. He would grow to be tall for the time, at six feet, with blonde hair and a distinctive forked beard.7 He was outgoing when he wanted to be, but also crippled by rigid ideas about honor and Habsburg etiquette. As an adult he carried a well-thumbed card with twenty-seven aphorisms to encourage good conduct, including “Be kind to everyone”, “Two hours exercise daily”, and “Take it cooly.”8 If he were born of this generation, Max would be a nepo baby try-hard—probably a productivity podcaster.

Charlotte Marie, known to history as Carlota, was not dissimilar. She was 16 when she met Max, and 17 when they were married in Brussels in front of 60,000 people. She, too, was aspirational. And she, too, had a bit of a monarchist chip on her shoulder. She was the daughter of King Leopold, a duke of the Saxon duchies who had been offered the throne of Belgium, which was then a newly-formed nation created, more or less, to stymie French territorial ambitions (an interesting parallel to Napoleon’s designs for Mexico against the U.S.). As such, Belgium was considered the youngest and least of the European monarchies. Carlotta wanted something more for herself. An empire in Mexico would do.

Before he would take the throne, Maximilian told Napoleon III that he had two conditions: one, France and Britain must sign a military alliance protecting the new kingdom and second, the Mexican people must declare a vote in his favor. On the first point, Napoleon III willfully misled Maximilian. As for the second, it may not surprise you that reports of the people’s desire for a European monarchy were greatly exaggerated. It will be further unsurprising that the Austrian archduke and his Belgian wife, so desirous of their own kingdom, accepted the monarchy anyway.

Odd ephemera of a forgotten empire

Maximilian and Carlota ruled for three years. Max spent much of that time hunting butterflies and issuing edicts that were never followed. Accustomed to Austrian authority and bureaucracy, he governed as if “The Empire of Mexico” were an established dominion, rather than a newly formed and precarious state propped up by conservative Mexican expats, French troops and, at least initially, the implicit support of the Pope. But the question of papal support was Max’s first blunder. Determined to establish liberal reforms, Max angered the church and Conservatives by decreeing freedom of worship, undermining the stability of his empire almost immediately.

It’s impossible to I really don’t want to summarize Max’s entire tenure, except to say this: you’d be surprised how liberal he was! He outlawed corporal punishment! He regulated child labor! Forever a fan of sandwiches, he even mandated lunch breaks! Importantly, he abolished debt peonage, the system where hacienda owners forced tenants to pay debts through labor. And, in direct opposition to Mexico’s ruling class at the time, he embraced the indigenous population, restoring rights to shared land ownership and had government decrees published in Nahuatl, the language of the Aztecs. Ironically, or perhaps tragically, Max’s policy positions were not dissimilar from those of Juárez, the indigenous and elected leader he deposed.

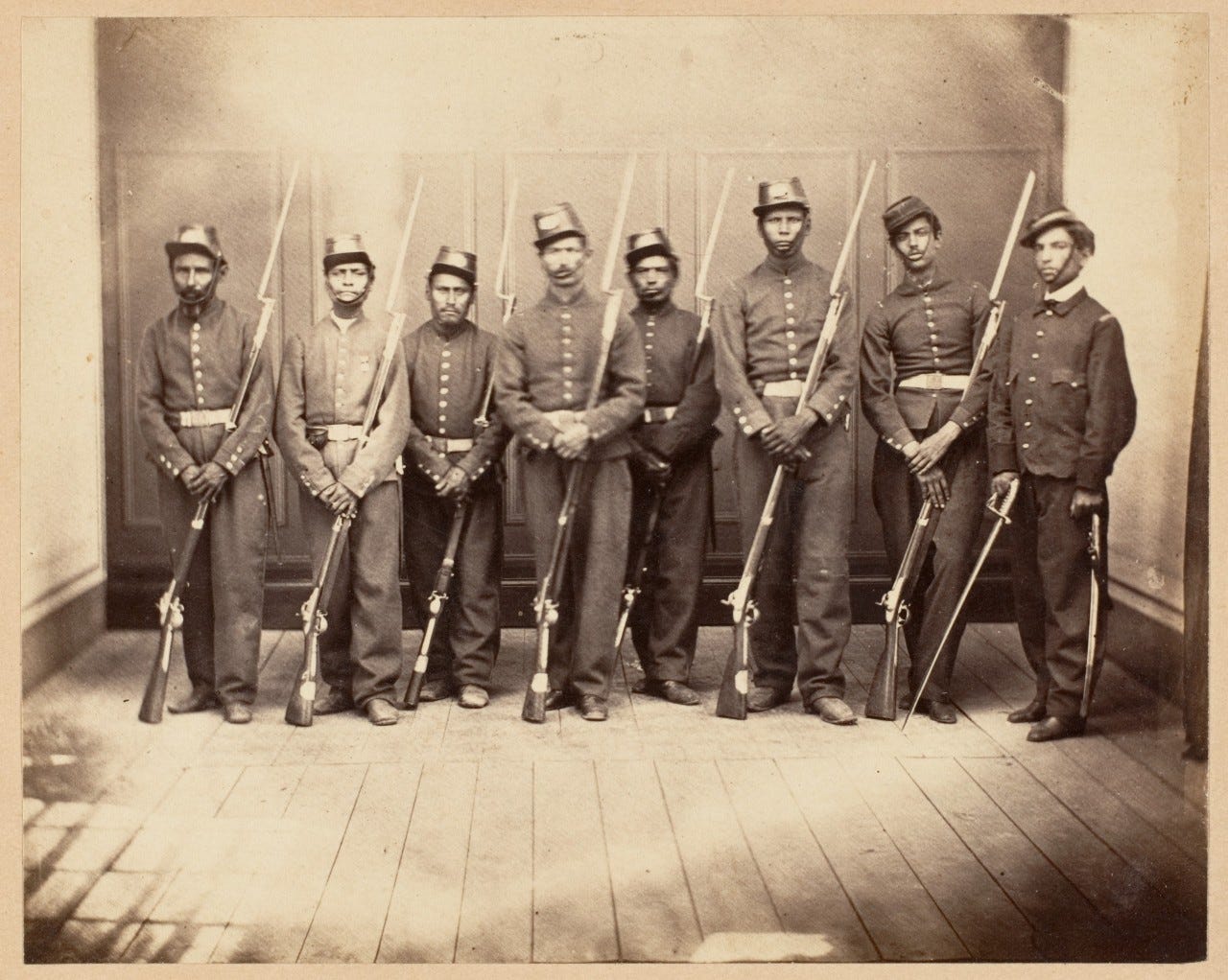

But ultimately, Max’s empire was a lost cause. The fact that the empire was predicated on foreign invasion didn’t sit well with Nationalists. Liberals didn’t enjoy its Conservative origins. And the United States, having concluded its Civil War, didn’t appreciate French forces in their backyard. Juárez’s forces, lurking in the hinterlands and with material support from the U.S., eventually overran the Imperial forces, which were mostly French troops and Austrian volunteers. Abandoned by France and outnumbered by Juárez, Maximilian was captured in Querétaro on May 15th, 1867. A month later he was executed.

Today what people mostly remember about Maximilian is his death. Manet’s famous painting of his execution, at a small church in Querétaro, depicts French troops (including one who appears to be Napoleon III) firing point blank. Max is wearing a sombrero. Manet created five works on how the would be reformer was betrayed by his former allies, all of which were brought together for an exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in New York in 2006.

Manet wasn’t at the execution himself, but French photographer François Aubert was. He produced several works, including a shot of Maximilian’s embalmed body in his coffin and a grisly photograph of Maximilian’s bullet-ridden shirt. That latter photo was used for a particularly grim carte-de-visite, a kind of memorial token or mourning object.

Maximilian is buried at the imperial crypt in Austria, but there is a small Roman Catholic chapel located on the Cerro de las Campanas in Querétaro City dedicated to his memory, built on the spot where the Emperor and two of his generals were executed. It’s about a three-hour drive north of Mexico City.

Or you could just walk down Reforma. Originally constructed for his imperial retinue, the avenue was intended to run from Chapultepec Castle to the National Palace, but that plan would have required demolishing a large area of El Centro. Instead, Max had it built to the site of El Caballito, a statue depicting Charles IV. Max decided to honor it—which is why, at that intersection, to my eternal frustration, Reforma stops going directly towards downtown and just kinda bends upward and away from Centro, contributing to a sense of where-the-fuck-do-roads-even-go-here. Today, El Caballito sits in front of the National Museum of Art. In its place, on Reforma, is a dramatically yellow steel sculpture of the same name that doubles as a steam vent for the sewer below. Not sure if that’s a metaphor.

As for the geopolitical consequences of Max’s brief reign, I’ll quote Edward Shawcross from his excellent book, The Last Empire of Mexico:

With Maximilian’s execution, intervention in Mexico was recognised as a cataclysmic failure months after the last French soldiers returned. A monumental gamble—outrageous even by the standards of European imperialism—Napoleon III’s policy unleashed yet more chaos and violence in Mexico and further impoverished a poor nation. As for the idea behind it, stopping US hegemony, it was the greatest challenge to the Monroe Doctrine until the Cuban missile crisis nearly one hundred years later; however, at the cost of billions of dollars in today’s money and thousands of lives, far from checking US power, Napoleon III was merely afforded the opportunity to witness it firsthand: forced to withdraw French forces from Mexico to avoid war with its northern neighbor.

With Maximilian and the French out of the picture, Juárez assumed the presidency in Mexico City again, but died a year later. Soon thereafter, one of his generals, Porfirio Díaz, rebelled and assumed the presidency. He would rule for close to 35 years as a de facto dictator, until his ouster ignited the Mexican Revolution.

So in a sense, French intervention brought a temporary stability in Mexico, but in a manner less imperialistic than it was, well, surreal.

🌙 Coming soon: The Moon Scar City Travel Guide

We’re building our itineraries and recommendations for Mexico City, including day trips and neighborhood guides. Is there any area of CDMX you’d like to know more about? Please make your requests the comments, or respond to this email! p.s., and only slightly related: we’re still figuring out the right publishing day and time for this letter; please be patient while we futz around a bit.

Moon Scar City is written by Steve Bryant, who lives and works in Mexico City. More about Steve at thisisdelightful.com.

The Constitution of 1857 was a liberal constitution that established individual rights, created a strong national congress, abolished slavery, and sought to abolish common land ownership by corporate entities like the Catholic Church, among other things. It also ended Catholicism as the official state religion. Conservatives opposed the enactment of the Constitution, which led to the Reform War.

Juárez deserves his own letter (really, his own newsletter) but for the sake of space and time, we’re going to save his story for another day.

A brief and incomplete but nevertheless diverting list of municipal improvements Napoleon III made to Paris: The construction of Les Halles, Gare de Lyon, and Gare du Nord, the creation and refurbishment of city parks, and the limiting of building height to four stories, lending them a picturesque consistency you can see today in, for example, the movie Inception and overpriced black & white postcards at Urban Outfitters.

José María Gutiérrez de Estrada and José Manuel Hidalgo deserve their own letter. Estrada, especially, as his itinerant weaselling was most responsible for promoting the idea of a Mexican Empire.

The Convention of London 1861 was and agreement between the UK, Spain, and France to seize custom houses on Mexico’s coast in order to recoup lost revenue. Britain’s prime minister, Lord Palmerston, was against meddling in Mexican politics, so he insisted on inserting into the Convention a clause that said the allies would do no such thing. Napoleon III, eager to get Maximilian’s buy-in, claimed that despite this clause Britain secretly supported France’s ambitions of regime change.

You don’t have to be a student of history, or even Game of Thrones, to appreciate the royalist playbook: have lots of children, marry them into prominent ruling families, and see them on a throne—regardless of whether they’re the sharpest cheddar on the cheese tray. So throughout history you have families like that of Queen Victoria, the so-called grandmammy of Europe, whose procreative enthusiasm led to, e.g., having two grandchildren occupying the thrones of the UK and Germany at the beginning of World War I, and another who was so touched that she fell in love with Rasputin, undermined the czarist state, and was summarily marched into a Yekaterinburg basement and shot through her diamond-studded bustier.

Y’know, I’m not sure how or even whether to mention the Habsburg jaw? When I was coming up, you wouldn’t hesitate to mock or at least mention a famous physical characteristic—but now it feels, what, cruel? Even if it is punching up! Anyway, Habsburgs famously had exaggerated mandibles that researchers believe were the result of inbreeding.

These details and many more in this letter were taken from Edward Shawcross’ excellent book, The Last Emperor of Mexico. New York: Penguin Press, 2019, Kindle