His hair, innocent of raindrops, which seemed almost lacquered, and a heavy perfume emanating from him, betrayed his daily visit to the peluquería; he was impeccably dressed in striped trousers and a black coat, inflexibly muy correcto, like most Mexicans of his type, despite earthquake and thunderstone. He threw the match away now with a gesture that was not wasted, for it amounted to a salute. “Come and have a drink,” he said.

—Malcolm Lowry, Under the Volcano

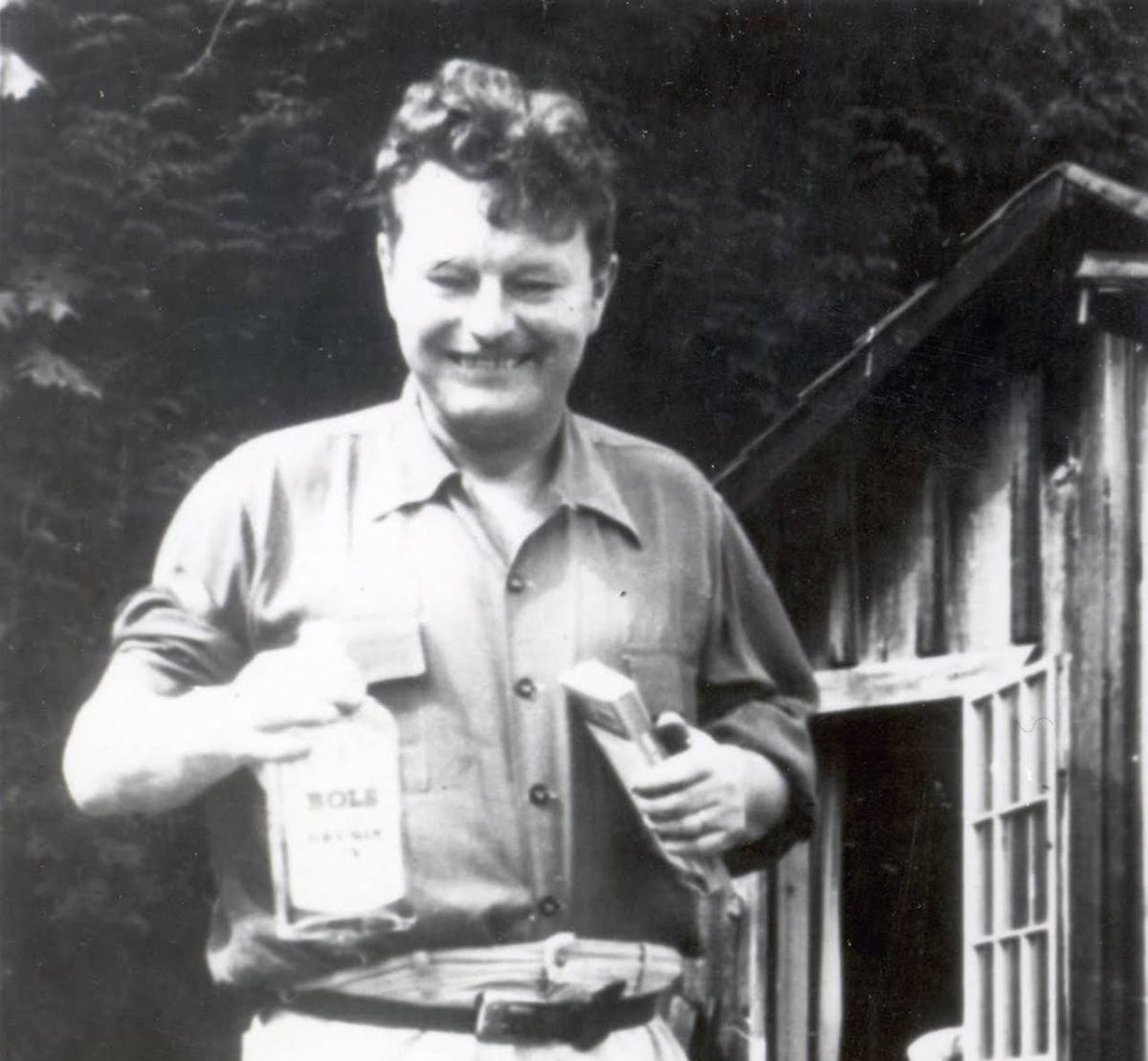

Malcolm Lowry the drunk, the boozer, the English writer who wrote a lot but rarely published mostly because he was drunk and boozing: he wrote and drank and boozed here, most of all, in Oaxaca.

What he was writing, between honey of maguey and tremors of the hand, was Under the Volcano: a novel about the last day of an irredeemably besotted consul that would become forever associated with Oaxaca.

The locals still talk about this, almost a hundred years later—that time when a famous Englishman got famously drunk!—and that’s what my friend Coco was talking about as we walked into Caminito al Cielo, a bar on the outskirts of the city center.

He used to drink here, Coco said, as we settled into a corner table inside a stucco and brick room decorated with knock-off oil paintings, framed news clippings, and plastic table cloths. Coco was born in Oaxaca, the son of a tour guide who, when Coco was six, abandoned the family to accompany tourists in other cities. Coco had since made good, married a Zapotec beauty and was, he said, about to pay off his house, where they’d be putting in a pool for his two kids. We’d been introduced by a friend in Mexico City and Coco, being a generous sort, had readily agreed to grab a mezcal or two during my visit.

I liked his choice of bars immediately. The waiter dropped off a torn menu, covered in ragged and stained plastic. You know a restaurant has been irredeemably americanized when there are no mistranslations on the menu: no “stepped on eggs”, no “divorced eggs”, no “spectral chicken of the house”. This menu, on the other hand, was on the other end of the spectrum; it had no translations at all and clearly hadn’t been changed in a decade, adding to the feeling of being somewhere off the gringo golden trail. For the table Coco ordered an ajo curtido, a delicious clove of preserved and oily garlic, and as we snacked with toothpicks I spoke out loud the tattoo on his right hand: El diablo está en los detalles. The devil is in the details.

“Just to remind myself that you have to pay attention to everything,” he said.

The waiter poured two mezcals and we talked about Lowry, who arrived here in 1937: Nazis ascendant in Germany, Franco dominating Spain, and the theocratic Sinarquistas trooping through Mexico, hunting communists. Lowry’s ostensible reason for traveling to Mexico was to rekindle his relationship with his wife, but he eventually left her in Mexico City in favor of the mezcal in Oaxaca—well, she left him, went to write scripts in Hollywood and send him doleful letters, pleading: fuck’s sake man, stop drinking, come here, or go to England, I don’t care, but lay off the mescal, pay your bills, maybe get psychoanalyzed, but whatever you do, get out.

He didn’t get out, except to the cantinas. When the maids at the Hotel Francia would no longer sneak him bottles of mescal in his room, he would sneak past the front desk, disguised under a blanket, to ride the pine at El Infierno (the hell), El Bosque (the forest), and El Farolito, which Lowry thought meant the lighthouse but really means “little light”.

Of course, we should say that although Lowry wrote parts of his novel here, Under the Volcano is set in Quauhnahuac, a fictionalization of Cuernavaca, where Lowry also kept a bed and a bar tab. Cuernavaca, for its part, used to be called Cuahuahuac, an Aztec word meaning “Near Wooded Mountains”. The Spaniards thought it sounded like ‘Cow-horn’, hence: Cuernavaca. And anyway all those bars in Oaxaca are gone now, the city has cobbled itself around them. Hotel Francia is a different hotel, El Farolito is now a Farmacias Similares where Mexico’s mascot and folk saint, Dr. Simi, dances in the afternoon sun. There is no Malcolm Lowry tour of Oaxaca, except the kind taken on a stool, one caballito at a time.

Now, please be assured that I know: Lowry is a dour topic, and his misadventures are not the Oaxaca one normally reads about in Tripadvisor dot com or the pages of Travel + Leisure, where editorial assistants wax peripatetic about the city’s spicy moles, the transcendent salsas, and the crispy tlayuda—those flour tortilla pizzas served in generous half-moon portions hot off the sarten. This is also the mountainous homeland of the Zapotecs and Mixtecs, not to mention the birthplace of Mexico’s two most famous presidents: Benito Juárez, who famously rose from an orphaned farmer to become Mexico’s lead reformer, and Porfirio Díaz, who famously rebelled against Juárez and ruled Mexico until the Revolution. It is very beautiful here, and there is much to be amazed by.

But for a certain type of reader and traveler, Lowry remains a signifier of Oaxaca as sinister inframundo, an occluding territory of indulgence and escape. He’s an avatar of the tortured poet who suffers for his art, something of an anachronism in an age of hustleporn and sponsored content tiktoks. Or as one biographer puts it, as if to address the self-sabateurs among us: “one recognizes the feeling he had of being picked out for punishment by cruel gods of his own invention, a theme which recurs throughout his poetry and fiction and which was borne out by many painful experiences.”

Lowry eventually left Oaxaca, divorced, remarried, and settled in Vancouver with his second wife, where he finished Under the Volcano and saw it published. It was also there that he suffered, in 1957 at age 48, one of the all-time great British euphemisms: “death by misadventure”. In eulogizing him, the philosopher William Gass beat no such bushes: “he rounded the world as a sailor, wrote a few strange stories, was twice married, and, perfectamente borracho, choked to death on his own vomit.” Beware Oaxaca, perhaps, is the lesson. But more precisely: beware thyself.

As Coco and I were walking out of Caminito al Cielo, I noticed that one of the clippings on the wall mentioned that the bar opened in the 60s. Though Lowry was known for being a prodigious jake-leg, I expressed doubt that his powers extended to the ability to return, posthumously, for a tipple.

“Well it was a different bar back then,” Coco said.

El diablo, los detalles, etc.

“But,” he said, regathering himself: “Do you know why it’s called Caminito al Cielo?” As we were walking towards his pickup truck he pointed down the street at the cemetery Panteón General. “The name of the bar means Highway to Heaven.”

Then we stood there and read the inscription over the gate: postraos: aqui la eternidad empieza / y es polvo aqui la mundanal grandeza.

Bow down: here eternity begins, and here worldly greatness is dust.

Recommended in Oaxaca

A few places we stopped into and can recommend

Caminito al Cielo: Cantina in a homely little space that seems like an abuela’s kitchen. Absolutely delicious ajo curtido.

Fito’s Bar: Bare bones cantina frequented by locals. Not pretty but a lot of fun. Gets the job done.

Selva Oaxaca Cocktail Bar: Fanciest cocktail joint in the territory. Reservations recommended. Get there at opening, 5pm, for one of only two balcony seats and a view of Templo de Santo Domingo de Guzmán (insta)

📕 What is Julian’s?

Julian’s is a handbook for curious travelers written by Steve Bryant, who lives and works in Mexico City. Julian’s is named for his grandfather and the wordmark is designed in Frustro, a typeface inspired by the Pemrose Triangle, and which represents impossible objects—appropriate for Mexico City, which Salvador Dali once described as more surreal than his art. Come visit us soon, we’d love to meet you.

Fantastic post about a classic book! Malcolm's words convey the social and cultural values that bring Oaxaca in the 1930s to life. Lowry certainly enjoyed his mezcal, and it's comforting to know that there's no liver damage from savoring the words on these pages.