To round out our brief Yucatan trip we took a morning van to Chichen Itza, compelled not only by a Chilango friend back in Mexico City—it’s very cool, wey—but also a sense of touristic inertia, the easy comfort of an air conditioned ride through a humid land.

“I want to forget my western outlook,” said the Swiss adventurer Ella Maillart, who crossed from Peking to Srinagar on camelback, and from Geneva to Kabul in an open-air car. “I want to feel the whole impact made on me by the newness I meet at every step.” Me too, Ella, but as much as I yearned for a non-gringo kind of experience, it turned out we wouldn’t have time to explore the peninsula’s abandoned haciendas this time. Instead: we’d visit the Mayans and walk, along with our fellow tourists, on well-trod paths.

When the conquistadors came this way in the 1520s, looking for gold to plunder and tribes to convert, they fought to subdue the Maya, who battled and harassed the Spaniards with flint-tipped spears, bows, arrows, and stones. Twenty years of lowland warfare and smallpox later the Mayans fled into the southern jungle, while the conquistador Francisco de Montejo y León the Younger used stones from their abandoned city of T'HŌ to build Mérida. That was 1542. Today in 2024 you can stroll the broad Paseo de Montejo in Mérida under the shade of everglade palms and eclectic-style French mansions, and stop to enjoy a cocktail while browsing designer fashions at Casa T'HŌ (”a concept house”). Salud to ancient civilizations, I guess.

Of course, it was Chichen Itza that was supposed to be the Spaniard’s regional capital—it offered a central location on the peninsula, the conquistadors thought, and plenty of stone ruins to use as building material. But months after the Spanish settled there, the Maya attacked and killed 150 of them, forcing Montejo to flee under cover of darkness. It was a terrible defeat, setting back the Spanish conquest of the Yucatan by years and reminding the Spaniards of the lessons of Cortez: nothing would be possible without allies. A Mayan lord eventually converted to Catholicism, creating an alliance, and Mérida and Campeche became the centers of Spanish commerce. Chichen Itza, it’s crumbling pyramid towering over the trees, would stay in ruins.

It wasn’t until 1843 that Chichen Itza first entered the popular imagination. That’s when John Lloyd Stephens, later one of the planners of the Panama Canal, explored the site with the artist Frederick Catherwood.

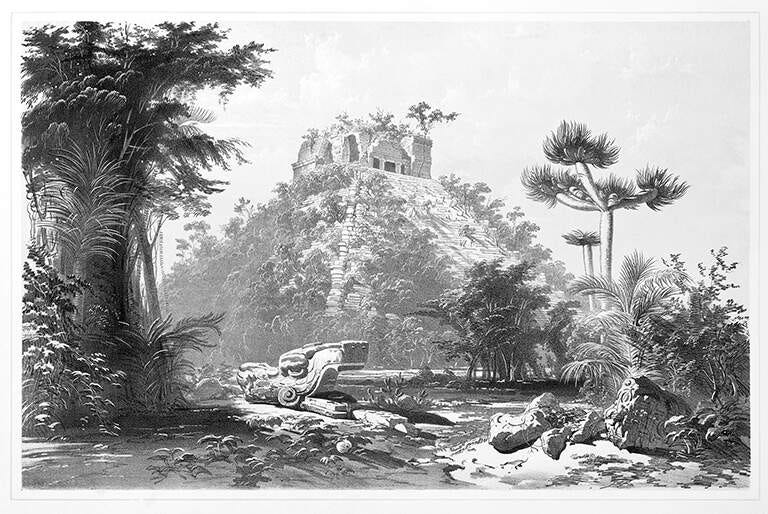

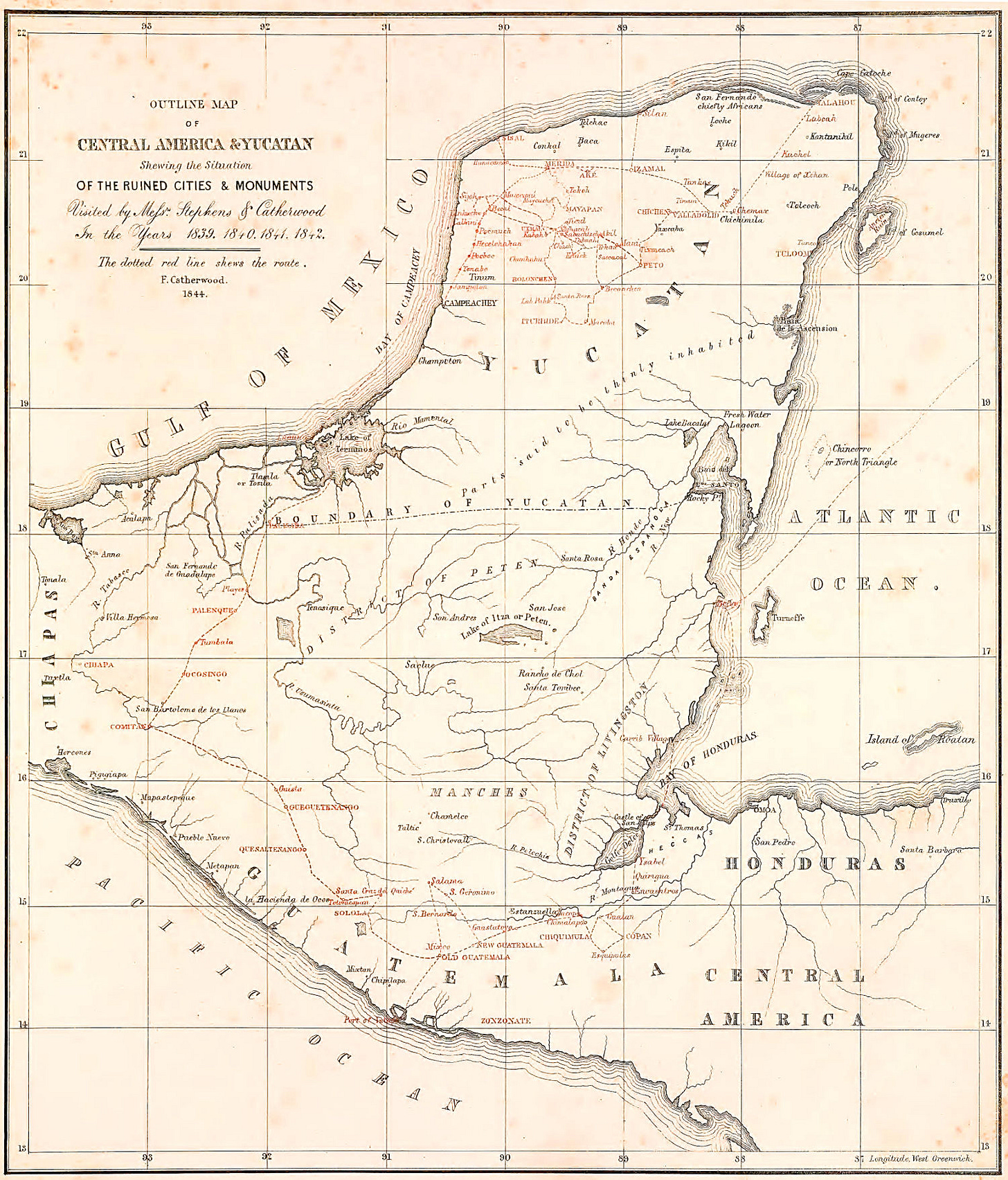

Stephens and Catherwood were the first foreign explorers to “discover” the Sacred Cenote where the Itza threw gold disks, jade figurines, beads, ornaments, pendants, and not a few young women and men, all in devotion to the god Chaac. If you’ve seen illustrations of Mayan ruins, dramatic images of moss-mountained pyramids and scowling stone warriors carrying spears and decked out in elaborate war feathers, those are Catherwood’s, who sketched in suffocating jungle heat with a camera lucida held up to his eye.

When they discovered these remains of the Mayan civilization, neither man knew anything of Mayan philosophy or the network of cenotes and underground rivers that watered the karstic lowlands. They had no idea about the Chicxulub crater that blew the ocean through the limestone, or of the Cocos plate that thrusts east and northward, ridging all of Central America with volcanoes, or of the hundred million Mesoamericans that had built interconnected civilizations long before Spanish explorers arrived. Earth still had its sequestered wonders. Charles Darwin hadn’t yet published On the Origin of Species. The Northwest Passage was still unconquered. The term archaeologist hadn’t been invented. Antarctica hadn’t been discovered, and many thought it didn’t exist. It’s largely the work of Stephens and Catherwood, whose books were read by Queen Victoria and exhibited during at least one World’s Fair, that compelled the world to realize the extent of pre-Spanish civilization.

Like Stephens and Catherwood, I knew none of this when I walked through Chichen Itza, only later stumbling upon Jungle of Stone, a breezy but detailed account of their bushwacking adventure through Honduras, Guatemala, Belize, and the Yucatán, mapping the Maya from Copán to Palenque. Almost two hundred years later anthropologists are still uncovering secrets—a pyramid and cenote hidden beneath Chichen Itza’s El Castillo were recently discovered—but what you’ll find on a tourist’s stroll, instead, are vendors selling faux onyx discs and factory-made “plástico mágico” masks. We strolled the paths, clapping our hands to hear the echoes and listening to the guides’ stories of sacrifice and magic. I felt badly that I hadn’t read more about the Maya. Their magic seemed, to me, far away and distant.

“Did you know the word hurricane comes from the Mayan,” my partner asked me a few days later. We were in bed, and she was leafing through a book of Mayan myths. “From Hurakán, one of the gods who created man.” And then: “Significa una pierna grande con cuernos.”

I raised an eyebrow and looked over at her.

“A giant leg with claws,” she said, and doesn’t that make a terrible kind of sense.

On my last morning on the peninsula, I woke up in an Airbnb, that a special kind of nowhere. Not my bed, not my sheets. Mérida is beautiful, but I was tired of a rented vibe.

I quickly washed my face, got dressed in Yucatán whites, and put my contacts in. Time to get some coffee, or maybe an early affogato. I was on my way to Sempere, a cafe and bookshop nestled above a street corner, to spend a few hours before my flight. The sun, still low in the sky, limed its way over the low house stonework. The streets were quiet. I could live here, is always the vacationer’s lament, bags already packed. Which is shorthand, always, for I could be different.

Instead of moving here, most visitors satisfy themselves with buying local fashions, Guayabaras and panama hats, that will rarely be worn again. They look wistfully down the street (I look wistfully down the street) at chipped paint and cracked stucco, faded painted signs, pebble smooth sidewalk curbs, and ask themselves: I wonder how much it would cost?

Half a million for a nice refurb, more or less. Real estate investors flocked here over the last ten or fifteen years; now, renovated homes in centro cost two-fifty, three, four hundred thousand. Airbnb boom maybe. Or that this town is ranked second safest in the Americas by something called CEOWorld magazine, which sounds like it was named by the same incisive minds behind Mattress King.

Deals can be had, of course. All of the home buyers, regardless, are obsessed with the same things I am: double height ceilings, deep and cool pools, fans shaped like palm leaves and colored tiles that look at times Moroccan, at times French, at times ornately Mayan. They love, we all love, what everyone loves: colonial architecture.

But what is colonial architecture? The colonial period in Mexico spanned three hundred years, 1521 to 1821. Hard to find buildings of that vintage here, save la Catedral de San Ildefonso, one of the oldest in the Americas (and built, in part, with Mayan stone). Art deco row houses are scattered about, but that’s early 20th-century. Same for the French-style mansion facades on the Paseo de Montejo, mostly built in the last years of the Porfiriato, with the wealth from hennequen plantations. Would you call those colonial? Not in time, not in style.

So really, when someone looks at the low row houses of Merida and says “colonial” they tend to mean, if we’re being generous, “neoclassical”. If we’re not: “gee, that looks old”. Keep that in mind, when looking at real estate listings here. “Colonial” is a cereal box selling point: Now packed with more vitamins and limestone minerals.

Which is to say: Colonial is just one of those words. An evocative catch-all for sentiment.

For white limestone, for the sound of a blue ocean lapping between green fronds. For women holding parasols, for iced tea and tropical cocktails on the porch, kept cool by a profitable trade wind. For a man in linen whites and a panama hat—a style born in Ecuador, actually, but never mind that, never mind.

My own white linen shirt is already soaked, I realize, as I climb the stairs to the coffee shop. I glance at my watch and already know: I’ll be ordering my first affogato before 11am.

-s.

Recommended in Mérida

A few places we stopped into and can recommend

Sempere: Coffee shop and bookstore tucked above the street. Excellent selection of Spanish books, and some in English, too. Coffee is 👌🏽. (insta)

Patio Petanca: Local spot for petanca (pétanque to francophiles) and cocktails that draws a young crowd (insta)

Caracol Púrpura: Best handcrafts in town (insta)

📕 What is Julian’s?

Julian’s is a handbook for curious travelers written by Steve Bryant, who lives and works in Mexico City. Julian’s is named for his grandfather, a very handsome southerner who never traveled anywhere, but who now has a travel newsletter named after him, so who knows where his namesake will end up. The wordmark for Julian’s is designed in Frustro, a typeface inspired by the Pemrose Triangle, and which represents impossible objects—appropriate for Mexico City, which Salvador Dali once described as more surreal than his art. Come visit us soon, we’d love to meet you.