Julian's, a Handbook for Curious Travelers

Join me as I create a more artful and interesting travel guide to Mexico City

Hey friend, welcome back to Julian’s, formerly Moon Scar City. Exciting news: we’re back in the saddle and writing a travel handbook to Mexico City! Before we get to those details though, I hope you’ll enjoy first the product of my last two months of deep research: a fun and diverting history of travel guides, which includes the invention of star ratings, the discovery of the dinner fork, the Nazi invasion of Norway, and how the 20th century’s most popular guide books were written by American spies. Researching this history inspired me to write my own handbook, and I have no doubt you’ll be surprised by what you read! Welcome back, it’s delightful to see you. And if you’re new here and enjoy history, art, and insights into Mexico, I hope you’ll use the button below to subscribe.

A brief and diverting history of the travel guide

I was mugged in Moscow, once.

This was twenty years ago. I was leaving a restaurant on a dark side street when a tall kid in a leather jacket pushed me up against a fence. It was 2am. He held my jacket in his fists and told me to give him all my money. Behind him, my friend Caitlin clutched a travel guide to her chest, its bright blue cover clearly visible: the Lonely Planet Guide to Russia. That moment, weirdly enough, is my defining memory of a travel guide—this particular one a comprehensive specimen which, though useless in the moment against a Russian thug, had probably, to its credit, advised both my friend and I, early in its pages, not to walk down a dark side street in Moscow at 2am.

Helpful suggestions like these have been a travel guide staple since 1836, when a fellow named John Murray III, in London, published the very first one.1 Red cover. Hard spine. Hundreds of pages. Timetables, routes, accommodation, restaurants, tipping, sights, walks, prices, all that stuff. The rational traveler’s rational resource, for a time when planning ahead meant sending your steamer trunk to arrive first, rather than sending a text saying you were running late. Murray’s A Hand-book for Travelers on the Continent was a reaction to the travelogues of the 18th century, which were often winding, first-person accounts about the experience of being in a country (vs. how to travel within a country), written by the bear-leaders of young aristocrats— i.e., British teenagers who were exploring the continent to learn about the world, often between the legs of sex workers.2 Murray’s was the first series to substitute the travelogue style of writing with curated itineraries designed to “ease a passage”. The man, bless his helpful heart, even invented star ratings.3

Murray’s trick was to put the reader first. He confined his reporting to what ought to be seen, rather than all that may be seen. This was the first step toward focusing a traveler’s attention on certain sights, the primordial ancestor of headlines that today include the words “must” and “see”. Murray also organized his recommendations by routes. Which boat to Antwerp, for example, and which road to Paris. In Paris, which inns were cleanest and, on the post-roads between Terracina and Mola-di-Gaëta in the Neapolitan territories, which were absent highwaymen. These were big concerns! Especially since the only fore-knowledge most travelers had of the continent came from the florid diaries of aristocrats, the purple reportage of newspapers and, occasionally, poems.

Murray’s handbook to the continent was the progenitor of what we call, today, the travel industry.4 But he wasn’t the most popular. That title goes to a German publisher named Karl Baedeker, who in the 1860s adopted several of Murray’s conventions (including, curiously, the same red covers5), and also used his own unique strategies: unlike Murray, Baedeker traveled to every location he wrote about, and he did it incognito to avoid biasing his reportage—Karl Baedeker, possibly the world’s first secret shopper. His guide books soon eclipsed Murray’s, becoming so ubiquitous that they were name-checked by EM Forster ("their noses were as red as their Baedekers") and TS Eliot ("Burbank with a Baedeker: Bleistein with a Cigar”), not to mention used by TE Lawrence during his archaeological digs in the Middle East. Bertrand Russell once confessed, somewhere, that he had two models for his prose style—Milton's and Baedeker's. By the 1920s, the verb “to Baedeker” had become a synonym for “to travel”.

If Murray’s first handbooks were successful because they arranged information for the traveler’s convenience, Baedeker’s were popular for their accuracy. A travel writer once described Baedeker’s guides as “made as if by spies, for spies”. Fact was, his books were used for purposes both espial and to, well, actually kill people. German’s invasion of Norway during WWII, according to a German military historian, was planned almost solely using the maps in Baedeker’s guides. Two years later, in response to British bombing raids, the German army (allegedly) said they would destroy everything in England that had “three stars” in Baedeker.6 The Baedeker Raids would stand out as the most prominent intersection of the military and the travel industry, were it not for the fact that the next generation of guide book publishers were, quite literally, American spies.

The spy who guided me

Eugene Fodor, an officer for the OSS during WWII, founded his eponymous company in 1949, a few years after he published On the Continent: The Entertaining Travel Annual. His goal at the time, to make travel guides just as fun as they are accurate, will be a revelation to contemporary travelers who’ve rarely read so powerful a soporific.7 Fodor’s immediate competitor was a fellow OSS officer in the psychological operations branch named Temple Fielding—a character seemingly out of an Ian Fleming novel who drove a convertible Cadillac around his adopted isle of Majorca, referred to himself by codename (“Ole Simon”), and carried his own vermouth. Fielding’s niche was to focus on creature comforts, rather than on the sights. Quite ahead of his time, this one: ''The fact is that most travelers don't give a damn for the sights, except for the very famous ones,'' he said. ''They pay lip service to museums, tombs, battlefields, but they care the most about their hotel - and if they're comfortable there, they generally like the city. Their second concern is restaurants and shopping. Sightseeing comes quite a bit down the list.''

Fielding was also—how to say this?—the wide-tied, over-sized lapel of voice, writing as though he were compiling an intelligence report for, e.g., spy lothario Dean Martin or, in later years, the Festrunk Bothers. I mean, just read the introduction to his 1956 guide, for Pete’s sake:

“Should US Steel stay up and USSR stay down—cross our fingers!—1956 will be the dizziest, busiest, merry-go-round in European travel history. If you climb aboard the carousel with a blueprint in your pocket and a twinkle in your eye, you’ll bring home the brass ring of holiday delight. But if your planning is faulty and your good humor stretches less than 12 inches, you’ll wish that you’d either gone with Aunt Mabel to Yellowstone Park or stood in bed.”

Is that a dick joke? Anyway, Temple Fielding died, appropriately enough, at 69.

Fielding and Fodor were followed by yet another enlisted F’er, Arthur Frommer, who, while serving in Germany during The Korean War, wrote the smash hit Europe on $5 a Day. The age of budget travel had begun. Guide books have since speciated into a genealogical tree of guides that have moved beyond simply reporting on what should be seen in a country, in lieu of focusing on the lifestyle of the traveler, and how to find that lifestyle wherever you go. Accordingly we’ve got guides for backpackers (Lonely Planet) and guides for European vacationers (Rick Steve’s), guides for progressives (Moon) and guides for beer drinkers, not to mention guides for credit card points maximizers, naked beach goers, typography stans, literature enthusiasts, and sex tourists.

The gringo golden trail

Of course, the great transiting that Murray’s guide books begat—tourists tourists everywhere!—is inspired less by books, these days, and more by top ten “must do” and “can’t miss” lists shared and texted and algo-sent to everyone. You don’t have to read a literal book when you travel, you only have to open Instagram or tiktok. And because everyone has instagram and tiktok and every thing on instagram and tiktok gets shared, everyone knows where to go, and everyone goes to the same places. When I first moved to Mexico City, a friend who had already been living here for a while asked me where I’d been eating. El Kaliman today, I said. Contramar tomorrow. She took a sip of wine and said well there you go, you’re already on the gringo golden trail.

The gringo golden trail! This is an actual thing! Well, it’s an actual metaphor, referring to an exaggerated thing—i.e., how all gringos, or gabachos if you actually want to be insulting, travel to the same beach towns, the same pueblos, the same mercados, the same bars. How deflating to disembark, water bottle firmly in hand, only to find that it’s not a foreign country you’re exploring, but a foreign IKEA. And these waypointed paths exist everywhere. Consider the Banana Pancake Trail, the default string of towns and cities that gringos follow in Southeast Asia, which was famously popularized by Lonely Planet8, before it was re-popularized by Leonardo DiCaprio9, long after it was, I guess you could say, “created” by an Englishman in the 16th century named Coryate, a.k.a. the world’s first backpacker—a barefooted fellow who breakfasted his way through the region, eventually returning to England by way of Italy bearing a great discovery: the dinner fork.10

Please be reassured: I’m aware that grousing about the flattening effect of tourism is not a new complaint. “All capitals are just alike”, moaned Rousseau in the eighteenth century, “Paris and London seem to me the same town”.11 Does that make me disingenuous then, or maybe boring, literal centuries later, for insisting that *something* about travel is different these days? A little less surprising? A little less fun? Maybe it’s the increased number of people traveling. Maybe it’s that we’re all using the same travel guides when we go. Maybe it’s we’re all using TikTok to plan which sites to see, then making more TikToks when we see them. Maybe, also, it’s the decreased effort of the occasion: Fewer steamer trunks and Verne-like voyages, more weekending in St. Barts or the Maldives with only a single pair of New Balance 550s on your feet. Briefer trips, smaller reasons to go, and much more of the going. Accordingly, the world has become quite a bit more recognizable, quite a bit less textured. In the fifties as people began to travel more often around the United States we got, at every interstate exit, a Howard Johnson. Today, as people travel around the globe on a whim we get, in every gentrifying warehouse district, six dollar cold brew.

Is this the fault of travel guides? I mean, big lol, no. Within the latticework of interconnected causes—more people, more money, more planes, more commerce, all of that—travel guides are hardly at fault for increasing the number of tourists. But, I will say this: they damn sure don’t help!

Since their creation in the mid-nineteenth century, guide books have existed in tension between two opposing ideas: on the one hand [holds up one hand], each publisher, without fail, promotes travel as an activity that broadens the mind. Murray’s first-ever guide, published in 1836, began with a page-long recommendation on the virtues of travel written by Francis Bacon, followed by a homily by the poet Samuel Rogers: “Our benevolence extends with our knowledge,” the latter wrote, “and must we not return better citizens than we went?”. Almost two hundred years later you’ll find a similar sentiment, albeit in slightly less florid language, in the pages of every Lonely Planet, of every Frommer’s, of every Rick Steve’s.

But on the other hand [waves other hand], while extolling travel as a humanist’s hobby, each publisher also focuses the attention of the traveler on the same foreign places and things. This is just as true for the listicles provided by online guides, e.g., Eater’s 38 Essential Restaurants in Mexico City, as it is for the actual books favored by older or more infrequent travelers, those gaggles of goose-necked Americans following recommendations for the most reliable hotels, the most dependable tours, the most delicious restaurants. Edify thy character abroad, both types of guides say, but please: only in the same places everyone else goes. Accordingly the “other” gets further and further away.12

Guide books are an inevitable consequence of travel, which would happen regardless. But the truth is I’ve never really cottoned to reading them. They are, all of them, useful (see e.g. the note about ways to avoid a mugging, at top), but they fail to evoke mystery or awe or a sense of the other, which is the great and grand idea of traveling. To increase our experience with the unfamiliar. To change ourselves by changing locations. Instead a guide book lays out, on its skin-thin pages, all the information a traveler could ever need about what to expect at a destination, how to get there, and which route to take, so that you may never be surprised. That’s not traveling, that’s Waze. In a 1950 interview, Swiss adventurer Ella Maillart said she liked to travel alone because any companion becomes “a detached piece of Europe”. The same can be said for guide books. When I pick up a guide book, I feel as though I’m carrying the United States with me.

Of course there are many different kinds of traveling, and the easy rejoinder to my complaint, which you will hear if you happen to whine about travel guides to friends, lovers, or disinterested bar patrons who are only trying to enjoy a long weekend away from the kids, is this: a guide book helps you prepare for the necessities, leaving you unhurried and unworried and better able to discover the parts of a foreign country that are sui generis. I’ll concede that point, and happily, though let’s be honest with each other dear friend / lover / bar patron: if you’re using a Lonely Planet or a Fodor’s or a Frommer’s, you’re more often likely to find the parts of a city that are sui in need of advance reservations or sui very much a discounted group tour. In more recent years I’ve read newer guides from Monocle and Wallpaper and Louis Vuitton, too, but they just do what the label says on the jar: focus on travel as the acquisition of affectations. You haven’t truly been somewhere, their curators suggest, unless you’ve bought selvedge jeans from a local craftsman (generationally wealthy), or eaten the banh mi tacos from a charming chef, (transplanted New Yorker with native roots) or, say, acquired an attractive tote bag (handcrafted from artisanal press releases).

Now look: I’m expressly not saying that travel is bad. I’m expressly not saying that tourism is bad. I’m expressly not saying that you are a tourist or saying, expressly or otherwise, that travel guides for tourists are sheep-bleetingly baaaaaad. What I very definitely am saying, though, is that travel guides don’t do what they purport to do. That is, they don’t help you to broaden your mind, to continually observe “new and unknown things” as Montaigne said in the 16th century; or “expand your horizons”, as Rick Steve’s says in the 21st century; or even, as my mom said last week while preparing for a trip to Oaxaca, “I am so tired of this bubble I live in, Stephen”.

Sorry mom, we live in an ever-bubbling bubble now.

Even Kazakhstan has Uber.

The commodity of place

And so now we come to the point. The value of a guide book, from Murray to Monocle, has always been in telling you *what to see* and *where to go*. If a guide does that well, if its details are accurate, you trust the brand. To this day, there is still value in that premise. The guide book industry hasn’t collapsed. People still use guide books, and merrily, because quite frankly they’re useful and damn convenient.

But the challenge is this: the information that Murray and Baedeker and Fodor and Frommer and Fielding all traveled across the world to obtain, that the inventors of Lonely Planet had to “discover” in hard-to-reach Southeast Asian places, that Rick Steve dutifully catalogues in his books—none of that information is hard to find now. The fact that Jenny from Minnesota, and several thousand people just like her, ranked the top five most romantic sundown spots in Sevilla isn’t going to put any of those guides out of business, but it does take a chunk out of their stated competitive position: namely, that they employ hundreds of freelancers who live in foreign countries and who have good taste and know all the good spots. But everybody is a freelancer, these days. Everybody knows all the good spots, these days. Because everybody, these days, can promote, in a matter of seconds, themselves and their experience to a far larger audience, than any guide book could ever reach, or even just ask whatever chatbot has replaced Google this week, what are the places I absolutely must see?

Accordingly, and this is really my big point here, the value of publishing *where to go* and *what to see* has decreased. Those are commodities. When the world has been scanned and Apple Mapp’d and LIDAR’d to every square inch, when every restauranteur and clothier who needs to promote their business can make tiktoks or insta-reels, or simply email the editor of The Infatuation saying look here, we too have Williamsburg prices, when the fruit vendors in the tianguis take payment by Venmo, then we’re all on the same monorail, we’re all getting off on the same stops. Looking for the other is like looking for an unscripted moment at Disneyworld. So now, if what you’re searching for is otherness, what matters isn’t the what to do or the how to do it, but the why. What matters is *why you’re here*. What matters is *why is this place different*. What matters is *a sense of otherness*. What matters is delight and surprise and a story well told. What matters is how travel changes you.

Freely admitted: few people want to leave the comforts of three hundred thread Egyptian cotton to take themselves bushwacking on some quixotic and misguided quest to find “otherness”, or more probably malaria. This is not an attractive proposition for, to take an example from personal experience, the members of the coastally-educated laptop class (of which I count myself as one). I agree with Fielding: most people just want a hotel room that doesn’t suck, and they want to post on socials that they’ve been there.

But! But, I am willing to bet that those same people would enjoy becoming more acquainted with the countries they travel to, above and beyond its restaurants and boutiques, if only they had convenient guides that provided that information. That’s my bet. That all the people I see in the fancy coffee shop below my apartment, buying six dollar cold brew, will also be entertained by a guide that helps them go deeper than, say, the difference between suadero and pastor.

And so that’s what we’re going to do here at Julian’s this year. We’re writing a travel handbook to Mexico City. We’re calling it Julian’s. And when I say we, I mean I. Julian is the name of my grandfather.

Julian’s will explore the turbulent history and magnificent arts of Mexico through ten of the city’s most popular sights and attractions.

That is, I’m putting the sights themselves first—these are, after all, the things that travelers come to see—and using those sights, in a kind-of walking tour format, to tell the kinds of deeply textured stories that are usually only touched upon in guide books. You’ll know what I mean if you’ve read some of our previous pieces, like Mexico’s Cistern of Sorrows or The “Gato Macho” who named Mexico City’s gay district.

Julian’s will be throughly researched, and the stories will be a delight to read. Actual facts, actually fun, not the voiceless monotone that’s so common in guide books. Julian’s will also be mercifully brief, the size of a chapbook, but after reading it you’ll be well versed in the history of the country and, accordingly, have more to talk about than how much you loved the overpriced taquitos at Contramar.

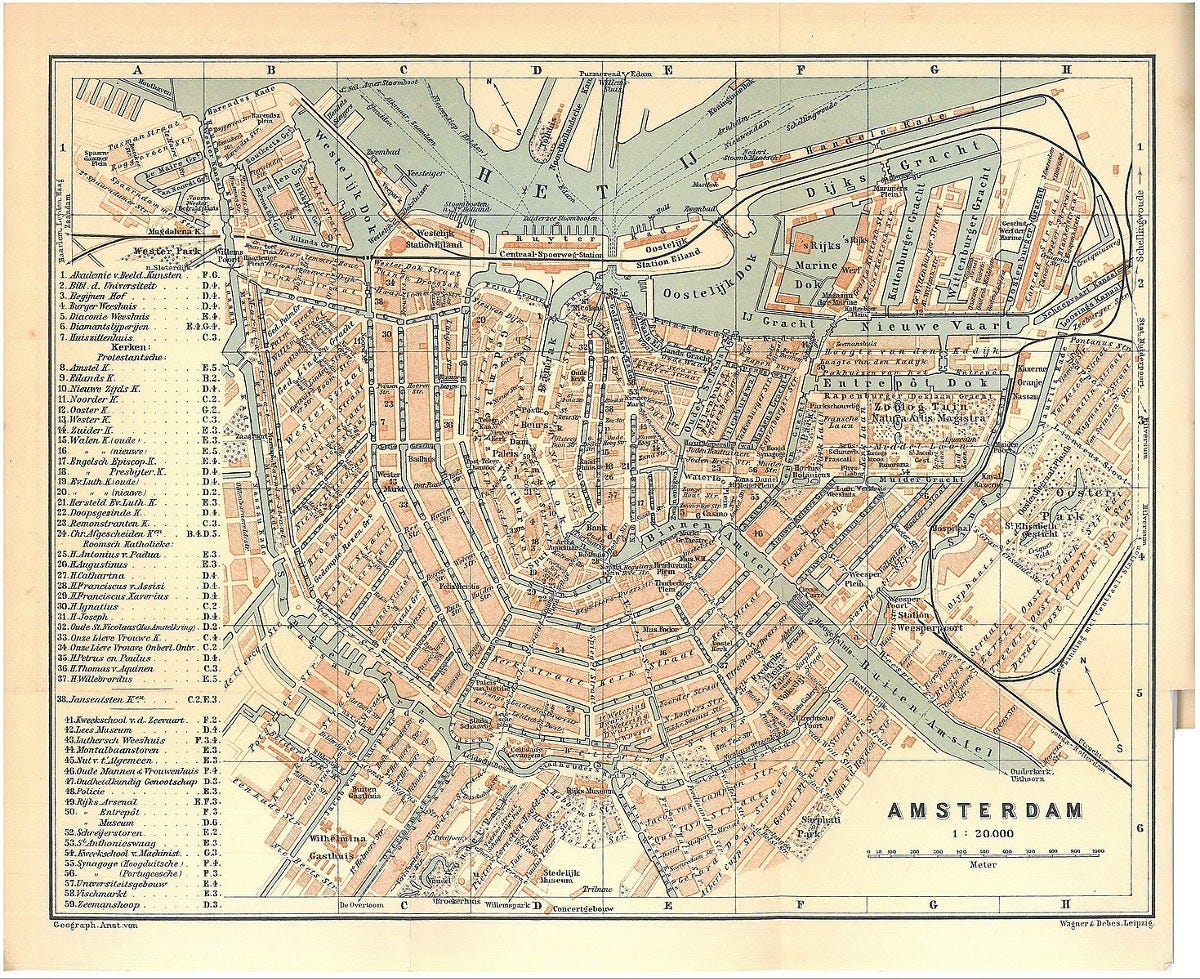

Julian’s won’t replace a city guide book, though, and it definitely won’t replace online trip planning guides. My goal isn’t to tell you everything you need to know. I trust you know best how to find great restaurants and hotels and tours. There is, after all <stretches arms wide> the internet. Instead, I’ll be going deep on the city’s most popular tourist attractions, using them to tell the stories you usually have to read a shelf full of non-fiction books for (happily enough, I’ve read them for you). The book will be designed to be read in an evening or two before you travel, or during your cafe breaks in the city itself, and it’ll provide resources for further discovery. Also a map. There will be a map.

The whole kit and caboodle will be printed in an attractive format, complete with original illustrations (see the example above), and made available online for ordering.

Below, a list of the chapters I’ll be writing this year.

I hope you’ll follow along as we publish them.

The chapters

Each chapter focuses on one attraction, using that attraction to tell a story about Mexico. The chapters proceed roughly in chronological order—that is, the handbook begins with the country’s indigenous roots, and proceeds to its perilous present. The chapters also form a walking tour. It’s possible to walk from the first site, el Zócalo, to the last, el Carcamo de Dolores, in a single day. It’s a long walk! But, for the prodigious, entirely doable. Enough preamble, here we go:

El Zócalo

A priority destination for Mexican politicians, foreign music acts, and unattended children, the Zócalo is an immense slab of pavement that was built above the previous civilization’s immense slab of pavementTemplo Mayor

When the Spaniards crossed down into the valley and first saw Tenochtítlan they were literally stunned: a Venice on a high mountain lake. Some of the soldiers turned to Cortes and Bernal Diaz and to each other and asked: is this not all a dream? It was, but it wasn’t theirs. The dream belonged to a people who called themselves the Mexica.Catedral Metropolitana

The conquest, the razing of temples, the Virgin of Guadalupe, and Mexico’s complicate relationship with CatholicismPaseo de Reforma

Mexico City’s main thoroughfare: built by the last emperor of Mexico’s to shorten his commute, paved by the last dictator of Mexico’s to burnish his reputation—to equal, he said, the Champs-ElyséesMonumento a la Revolución

What happens when you overthrow a dictator while he’s building a new houseEl Monumento de Cuauhtémoc

The tragic story of Descending Eagle, the first man to defend the patria from foreignersEl Ángel de Independencia

Mexico City's most recognizable landmark is home to revelers, protestors, tourists, and the pilgrim bones of Mexico's heroes of independenceLos Niños Heroes

The Mexican-American War, the invasion of Mexico City, and the children fighters who, according to the legend, lost their livesEl Castillo de Chapultepec

Built by the man who gave the city of Galveston its name, later home to Mexico’s last emperor, and today a helluva art museum. More of a palace, really.El Carcamo de Dolores

The art museum (and terminus of an engineering marvel) where Mexico City celebrates its toxic relationship with water

We’ll be publishing all of these chapters this year, along with weekly letters from my travels around the city and country, learning about the history of both. I hope you’ll follow along.

🌙 What is Julian’s?

Julian’s is an ongoing attempt to make a new kind of travel guide for people who care deeply about history. No restaurant recommendations. No tourist claptrap. No must-buy, get-the-look, digital nomad bullshit. Julian’s is written by Steve Bryant, who lives and works in Mexico City. More about Steve at thisisdelightful.com.

Footnotes

Charles Murray III came from a publishing family. In his lifetime he would publish Charles Darwin’s On the Origin of Species, Melville’s first two books, and Charles Eastlake's first English translation of Goethe's Theory of Colours. His father had published Jane Austen and Lord Byron. His father also burned Byron’s memoirs to prevent the revelation of scandalous details which would damage his (Byron’s) reputation. The contents of those memoirs, still unknown, remain one of literature’s great mysteries.

Infamous cad James Boswell (biographer of Samuel Johnson) and Lord Chesterfield, among others, remarked on the pleasures to be had on the continent. See the chapter “Why did Tourism start? Sex, Education, and The Grand Tour” in The Meaning of Travel (Emily Thomas, OUP Oxford, 2020)

For those he was inspired by his own client, Mariana Starke, who’d used a rating system of one to three exclamation points in her 1820 travelogue and guide, Travels on the Continent. Starke, in similar fashion to the Grand Tour-takers preceding her, considered her personal experience on the continent to be the greatest recommendation for her book.

Probably you’d say the other father of modern travel was Thomas Cook, a Baptist preacher credited with creating the first organized group tours to Europe in 1855.

For about a century there, between Murray’s 1836 guide and Michelin’s guides in the 1920s, travel book brands could be distinguished, more or less, by their covers: Red for Baedeker, Red and Green for Michelin, Blue for Blue Guides. Visible in traveler’s hands wherever they went, travel guide covers were the best advertisement a book could ask for.

Much of the above was sourced from a wildly thorough 1975 article in The New Yorker called “House of Baedeker”.

That was kinda mean. But also, have you read a Fodor’s lately? The original, published in 1936, was a hoot. It seems to begin with a hypothetical story about a man in Brussels who, desiring to hook up with an old flame in London, uses the guidebook to give her directions. It’s impossible to quote except at length, but you can read it in full at the Internet Archive.

Lonely Planet founder Tony Wheeler on the origins of the guide book: “We intended to go around the world in a year, live in Sydney for three months and come back to London. But even before we arrived [in Australia] we thought we’d make it a longer trip and spend three years away. We drove from London to Afghanistan in an old minivan and then made our way through Asia to Australia. While we were living in Sydney, we’d meet people [who’d ask about the trip] and they’d say what did you do, how did you do this, and we’d jot notes down for them. Back then the phrase “gap year” hadn’t been invented. There were people doing it, but the numbers [were much smaller] than today. So the first book was an accident. We both had full-time jobs in Australia – I was managing market research for Bayer Pharmaceuticals and Maureen was a PA at a wine company – and worked on it during the evenings and weekends. Then I took a day off work and went to some bookshops and said, I’ve written this book, do you want to buy some copies? And they did. It was called Across Asia on the Cheap. It got a couple of good reviews, and it sold 1,500 copies in a week. That was just in Sydney, although we took it to Melbourne and further afield soon after.”

In his 2000 film, directed by Danny Boyle, The Beach, which is not as good as I remember it being

In Rousseau’s Emile, or on Education (1762), Book 5, readable in full here.

“Self-discovery through a complex and sometimes arduous search for an Absolute Other is a basic theme of our civilization, a theme supporting an enormous literature: Odysseus, Aeneas, the Diaspora, Chaucer, Christopher Columbus, Pilgrim's Progress, Gulliver, Jules Verne, Western ethnography, Mao's Long March. This theme does not just thread its way through our literature and our history. It grows and develops, arriving at a kind of final flowering in modernity. What begins as the proper activity of a hero (Alexander the Great) develops into the goal of a socially organized group (the Crusaders), into the mark of status of an entire social class (the Grand Tour of the British "gentleman"), eventually becoming universal experience (the tourist).” — Dean MacCannell, The Tourist: A New Theory of the Leisure Class (New York 1976)